Kathleen O'Hara, Collections Manager and Registrar, recently revealed some of these objects. Here are some of the highlights:

Iroquois war club, Schnieder's Saloon

Beer barrel, Schieder's Saloon

What would a German saloon be without a beer barrel? Nineteenth century German saloons were family-friendly gathering places on the Lower East Side. While beer may have been the main attraction for parents of both sexes, whole families gathered in saloons like the one at 97 Orchard Street to enjoy home cooked meals and a lively atmosphere after a long day.

Sash and bundle of sticks, Schnieder's saloon

These objects are part of the regalia associated with the Oddfellows, another fraternal organization that congregated in the back rooms of saloons on the Lower East Side. The sash is made of velvet with intricate beaded designs. The bundle of sticks is a symbol which can be traced to ancient Roman concepts of strength and unity.

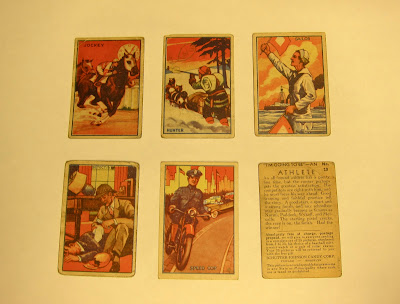

Trading Cards

These trading cards from 1934 were manufactured by the Schutter Johnson Candy-Corp. Collectors of all 25 designs could trade the cards in for various prizes such as a baseball mitt, a wristwatch, or roller skates. Cards depicting a detective, a policeman, a jockey, a hunter, a sailor, and an athlete are included in the Tenement Museum’s collections.

Microphone, Max Marcus' Auction House

A microphone like the one above would have been used by auction-house owners like 97 Orchard Street’s Max Marcus. The microphone, when plugged into a radio, would broadcast the auctioneer’s voice throughout the room. In this image of Marcus' crowded auction house from 1933, we can imagine that it might have been hard to hear Max’s voice even with the microphone!

Undergarments, Sidney's Undergarments

In the 1970s, the Meda family started their own business in the basement of 97 Orchard Street selling ladies undergarments, called Sidney Undergarments Co. These colorful underwear were given to the Museum by the Medas themselves. While these objects will not be on display for Shop Life, they give the curatorial team insight into the styles and prints that were popular at the time.

This is just a fraction of the cool items we have as part of our "Shop Life" collection. We'll keep you posted as we get closer to the exhibit's opening on October 1!

-- Posted by Ana Colon