Please direct further questions to events@tenement.org.

Showing posts with label lower east side history. Show all posts

Showing posts with label lower east side history. Show all posts

Monday, June 27, 2011

Wednesday, November 17, 2010

Our Neighbor on Broome Street

THIRTEEN / WNET has a web series called City Concealed, in which they visit lesser-known New York landmarks. Their latest video concerns the Kehila Kedosha Janina synagogue here on Broome Street. Since 1927, the temple has been the spiritual home of the Lower East Side's Romaniote Jews, who came from the town of Ioannina (Yanina / Janina) in Greece. Neither Ashkenazi not Sephardic, this group has their own language and cultural traditions, although they worship in much the same way that all Jews do.

My favorite part of the video comes as the congregation members are discussing the foods of their culture, naming them one by one. As they get to fasolia, which someone says means "beans," congregation member Jerry Pardo interjects his own very personal memory of the dish:

"Fasolia's not just beans. Fasolia is your mother in the kitchen, five o'clock in the morning, Friday morning, with a cigarette hanging outta her mouth, and the beans are on the stove. They're simmering, and they're simmering, and they're simmering, and they're simmering, and there's pieces of lamb in it - the one that your father sucks the middle out of it, the marrow."

This dish isn't just some pot of beans - it embodies his mother's labor and love, her devotion to her culture and her family, and the special work she put into the weekly Sabbath meal.

The City Concealed: Kehila Kedosha Janina from Thirteen.org on Vimeo.

The synagogue is open for services and also open Sundays for guided tours of their small museum. Check it out next time you're in the neighborhood.

- Posted by Kate

My favorite part of the video comes as the congregation members are discussing the foods of their culture, naming them one by one. As they get to fasolia, which someone says means "beans," congregation member Jerry Pardo interjects his own very personal memory of the dish:

"Fasolia's not just beans. Fasolia is your mother in the kitchen, five o'clock in the morning, Friday morning, with a cigarette hanging outta her mouth, and the beans are on the stove. They're simmering, and they're simmering, and they're simmering, and they're simmering, and there's pieces of lamb in it - the one that your father sucks the middle out of it, the marrow."

This dish isn't just some pot of beans - it embodies his mother's labor and love, her devotion to her culture and her family, and the special work she put into the weekly Sabbath meal.

The City Concealed: Kehila Kedosha Janina from Thirteen.org on Vimeo.

The synagogue is open for services and also open Sundays for guided tours of their small museum. Check it out next time you're in the neighborhood.

- Posted by Kate

Labels:

building histories,

Jewish,

lower east side history,

Media

Monday, October 18, 2010

Looking Back at the Forward Building

During the early part of the twentieth century, many of the Yiddish-speaking immigrants who flooded the Lower East Side looked to famed newspaper The Jewish Daily Forward, or Forverts, for news and a gateway to American culture. First published on April 22, 1897, the socialist newspaper greatly influenced the political leanings of early Jewish immigrants and, by 1912, as readership exploded, The Forward became a leading national newspaper. Under the outspoken leadership of Abraham Cahan, a member of the Social Democratic Party of America, the paper continued to gain readers with its politics and increasing focus on issues close to the hearts and minds of workers, such as the crusade for labor unions.

It was during this era, amidst a frenzied competition with Russian-Jewish bank owner Sender Jarmulowsky to build the tallest structure on the Lower East Side, that the newspaper erected its headquarters at 175 East Broadway. Though falling short of the Jarmulowsky Bank's twelve story limestone and terracotta giant, architect George Boehm's Forward Building was nevertheless an impressive feat and cemented the paper's importance to the predominantly Jewish neighborhood. For a time, East Broadway even became known as "Yiddish newspaper row."

Readership waned in the decades after the 1920s, despite steps to modernize the paper. With the Red Scare, the paper pulled back on socialist politics in favor of a less radical liberal bent. Immigration from Yiddish-speaking countries was also on the decline, meaning fewer Jewish Lower East Siders and fewer readers. During the 1960s The Forward launched an English-language version to reach new audiences, and by the mid-70s, there was little reason for the paper to remain on East Broadway. The Forward left its original home, moving to midtown. The building's new tenants opened a church and community center for the growing Chinese population of the Lower East Side.

Taken in the seventies, in the wake of the newspaper's departure, the following photograph provides a closer look at the building's ornate facade, which retained its original marble and stained glass flourishes. You can also see the carved portraits of socialist heroes Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx, and Ferdinand Lasalle on either side of the "Forward Building" sign above the entryway.

|

| Collection of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum (c) 2010 |

|

| Collection of the Lower East Side Tenement Museum (c) 2010. |

The Forward, now a weekly magazine, was located at East 33rd Street until recent years when that building too was sold to developers looking to build luxury condos. Currently housed at 125 Maiden Lane in New York's Financial District, The Forward is still an influential news source, particularly for Jewish Americans, though its circulation is only about a quarter of what it was during the paper's glory days.

To see the historic Forward Building for yourself, make sure to take Immigrant Soles: A Neighborhood Walking Tour. Educators can tell you more about the paper's importance for the Lower East Side's early Jewish residents. The tour is offered daily. Get your tickets today!

- Posted by Joe Klarl

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

Questions for Curatorial: Orchard Street's Early Days

Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions.

Was 97 Orchard Street the first tenement to be built on the block?

By 1828, there were structures on all thirteen lots on the western side of Orchard Street between Broome and Delancey. Except for a church and the building on the corner of Broome Street, which was probably a multifamily residence with a store on the ground floor, all were mainly residential. For the most part, these were two-to-three story wood frame dwellings which by the 1850s were being used as multifamily residences.

Initial development of the 97 Orchard Street lot began with the erection of a Reformed Dutch Church in 1828, which stood on what is today 95, 97, and 99 Orchard Street. In 1860, the Dutch Reformed congregation sold the church to a Universalist congregation, who not long after sold it again to the Second Reformed Presbyterian Church.

Three years later, in 1863, the property was purchased by Lukas Glockner, Adam Strum, and Jacob Walter. The new owners demolished the church structure, for the 1864 Orchard Street tax rolls list three new five-story tenements on the lots, one belonging to each of the buyers. [Editor: Can you see the headline today? "High Rise Housing Development Destroys Church"]

As only one-fifth of the buildings located in the 10th ward were tenements, 95, 97, and 99 Orchard Streets are the earliest surviving tenements on the block bounded by Broome and Delancey.

Was 97 Orchard Street the first tenement to be built on the block?

By 1828, there were structures on all thirteen lots on the western side of Orchard Street between Broome and Delancey. Except for a church and the building on the corner of Broome Street, which was probably a multifamily residence with a store on the ground floor, all were mainly residential. For the most part, these were two-to-three story wood frame dwellings which by the 1850s were being used as multifamily residences.

|

| 95, 97, and 99 Orchard Street circa 1999. Collection of LESTM. |

Three years later, in 1863, the property was purchased by Lukas Glockner, Adam Strum, and Jacob Walter. The new owners demolished the church structure, for the 1864 Orchard Street tax rolls list three new five-story tenements on the lots, one belonging to each of the buyers. [Editor: Can you see the headline today? "High Rise Housing Development Destroys Church"]

As only one-fifth of the buildings located in the 10th ward were tenements, 95, 97, and 99 Orchard Streets are the earliest surviving tenements on the block bounded by Broome and Delancey.

Monday, August 2, 2010

Their Backyard: Children of the Lower East Side

It's summertime and school's out. Lots of city kids are spending their vacations playing games outside, venturing to summer camp, or mastering ever popular video games to pass the time until the new school year begins. School wasn't always mandatory, until the Compulsory Education Law of 1894 required that children 8 to 12 years-old attend school full-time. [Read more.] Josephine Baldizzi (a resident at 97 Orchard from c. 1928-1935) recalled that the schools were the facilities most utilized by her family. [Read more.] That made me wonder, how did children of the Lower East Side spend their time outside of school? I’ve pulled a few photographs that capture what life was like for the children of the tenements in the mid-20th century to give you a taste of the incredible visual material now available on the museum's online photo database.

Kids playing hookey from school c. 1948

Young boys play on a tenement building c. 1935

Boy sits looking out over a tenement rear yard c. 1935

Boy and girl on Clinton Street c. 1946

Haven't had a chance yet to browse the photo database? Search for other keywords of interest (e.g. the street you grew up on or “Baldizzi” or “fire escape”) to learn more about the history of the Lower East Side.

-posted by Devin

Kids playing hookey from school c. 1948

Young boys play on a tenement building c. 1935

Boy sits looking out over a tenement rear yard c. 1935

Boy and girl on Clinton Street c. 1946

Haven't had a chance yet to browse the photo database? Search for other keywords of interest (e.g. the street you grew up on or “Baldizzi” or “fire escape”) to learn more about the history of the Lower East Side.

-posted by Devin

Thursday, May 20, 2010

A former streetscape revealed in destruction on Grand Street

Our Minding the Store project manager, Chris Neville, has been researching the businesses that operated out of 97 Orchard Street from 1863 to 1988. As such, he's become mildly obsessed with the streetscapes of the Lower East Side. He thinks a lot about facades and buildings and how businesses incorporated themselves into tenements. He looks all the time for evidence of how stores in the earlier part of the 20th century, and even into the 19th century, might have set up their spaces. We don't have a lot of documentary evidence about the businesses in 97 or the building's facade, so we look around the neighborhood for similar tenements, checking for the layers of physical fabric that so often exist in older neighborhoods.

His eyes attuned to notice architectural details, Chris right away noticed some markings on the brick walls of the tenements next door to the two that were demolished recently, after the deadly fire on Grand Street. He did some research and discovered what existed on those lots before the tenements were constructed in the 1890s.

Head over to Bowery Boogie to read his post.

His eyes attuned to notice architectural details, Chris right away noticed some markings on the brick walls of the tenements next door to the two that were demolished recently, after the deadly fire on Grand Street. He did some research and discovered what existed on those lots before the tenements were constructed in the 1890s.

Head over to Bowery Boogie to read his post.

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

See you at the Confetti Dance?

Educator Allison Siegel continues her research into buildings on the Lower East Side. At the request of curious Tenement Museum staffers, she looked into 345 Grand Street, a cast iron building at the corner of Ludlow.

My first attempt at researching 345 Grand Street brought me to an interesting blog called Coretalks.com. Click to read more, but in a nutshell, over the years the building was a dance hall and a piano showroom.

I was immediately obsessed with finding out more! Could this building have been all that was claimed?

I was able to confirm H.W. Perlman’s Piano outlet was there, but was unsuccessful locating when. After hours of research, I caved and contacted the author of the blog, David Grossman, who put me in touch with one of the previous owner of the building. Here’s what he had to say:

(I am working on continuing Mr. Frazer’s research of Little Willie and Big Sam Kaplan and The Confetti Dance- stay tuned for what I find!)

While Mr. Frazer couldn't specify years, he did provide me with a ton of additional info to research, and so I did…

Not only was there a dancehall at 345 Grand, but when the building opened between Dec. 2 and Dec. 8, 1888, it did so as a “combination museum, theatre, menagerie and aquarium” in 1888.

‘til next time.

-A. B. Siegel

Thanks to Coretalks.com for the images.

My first attempt at researching 345 Grand Street brought me to an interesting blog called Coretalks.com. Click to read more, but in a nutshell, over the years the building was a dance hall and a piano showroom.

I was immediately obsessed with finding out more! Could this building have been all that was claimed?

I was able to confirm H.W. Perlman’s Piano outlet was there, but was unsuccessful locating when. After hours of research, I caved and contacted the author of the blog, David Grossman, who put me in touch with one of the previous owner of the building. Here’s what he had to say:

Hello Allison,

David's article tells you most of what I know about the building. The exterior photo from around 1900 was retrieved from NY City archives by another owner, David Rakovsky on the 4th floor. When I was negotiating to buy the building in 1999, a man named Jimmy, who had been employed as a super by the owners Alan and Alice Friedman for many years, told me there used to be a dance parlor in the place, and with nods and winks he suggested that where there was dancing, there was probably a brothel too. I have no idea if that's true as a generalization, let alone true for 345 Grand.

In any event, the dance ticket we discovered under the floorboards confirms that the 2nd floor was a dance hall, and the stairway that used to connect the 1st and 2nd floors suggests that it might have occupied both floors -- perhaps a lounge or smoking room downstairs? We Googled the performers, Little Willie and Big Sam Kaplan, and contacted a few Kaplans with a LES background but learned nothing more. We surmise that a confetti dance had the band playing a medley -- a polka, a waltz, etc -- and there's an 1889 short film cited on Google called The Confetti Dance, but no information about it.

That's about all I know, except for a few half-credible stories about Lou Reid and Blondie having (at different times) lived next door or behind us, on Ludlow.

cheers

Phillip Frazer

(I am working on continuing Mr. Frazer’s research of Little Willie and Big Sam Kaplan and The Confetti Dance- stay tuned for what I find!)

While Mr. Frazer couldn't specify years, he did provide me with a ton of additional info to research, and so I did…

Not only was there a dancehall at 345 Grand, but when the building opened between Dec. 2 and Dec. 8, 1888, it did so as a “combination museum, theatre, menagerie and aquarium” in 1888.

“THE GRAND STREET MUSEUM A VERY humble east side place of amusement was THE GRAND STREET MUSEUM situated at Nos 345 and 347 Grand Street It was opened Dec 8 1888 and besides the living and other curiosities to be seen there dramatic performances were given and all could be enjoyed for ten cents.”

A history of the New York stage from the first performance in 1732 ..., Volume 2Yet another intriguing piece of New York City’s history, and folks, if you fancy yourself a new condo (FYI: according to the NY City Register, the building converted to the Grand Digs Condominium on April 8, 2003) -- some of the units are up for grabs.

By Thomas Allston Brown

Page 591

‘til next time.

-A. B. Siegel

Thanks to Coretalks.com for the images.

Labels:

building histories,

lower east side history,

Music

Tuesday, March 16, 2010

More Berenice Abbott on the Lower East Side

A stretch of Grand Street (no.s 511-513), outdated in 1937 when this photo was taken, that, miraculously, still stands.

View Larger Map

View Larger Map

Thursday, March 11, 2010

More from the Berenice Abbott Collection

A roast corn man, at the corner of Orchard and Hester (courtesy NYPL). May 3, 1938.

As of December 1, 1938, most forms of street vending were outlawed in New York City. Along the lines of Abbott's other photos, this was part of the "changing" city. Two vendors are clearly seen street peddling, despite the ban.

Read more (pdf) from Suzanne Wasserman, head of the Gotham Center for New York City History.

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

Questions for Curatorial: Business in the Tenements

Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions.

What businesses operated out of 97 Orchard Street over the years? How do you know?

The Museum's researchers use many different sources to find out about the history of our tenement building. City directory records, newspapers, factory inspector reports, and oral histories are just a few of the resources available to us when researching retail or manufacturing businesses.

For instance, the 1917 city directory records the following businesses occupying the storefronts spaces of 97 Orchard Street:

1929:

Fisher, Harry Hosiery

Fischer & Schimmel Hosiery

Orchard Printing Co.

Scher, A. General Merchandise

Schimmel, Rubin Hosiery

Solomon, L Printer

1930:

Fischer & Schimmel Hosiery

Scher, A. General Merchandise

1931:

Reliable Jobbing Co.

S & D Underwear Corp.

Scher, A. General Merchandise

1933

S & D Underwear Corp.

Scher Jobbing House

Scherm Wm Jobber

1934

Duberman, H. Handbags

Scher’s Jobbing House Inc.

Scher’s Jobbing House Inc.

Seaboard Impt. Co.

1935

Duberman, H. Handbags

Gips & Mendesohn Inc. Hosiery

Seaboard Impt. Co.

1937

Auction Exchange

Gips & Mendesohn Inc. Hosiery

1939

Brandies, Herman Auctioneer

Brandies & Marcus Merchandise

Gips & Mendesohn Inc. Hosiery

1940

Gips & Mendesohn Inc. Hosiery

Scher, Wm. Auction Outlet

Does anyone want to share what a "jobber" is? I bet some of you readers know. Or worked as a jobber even?

Some of these businesses, including the auction house, will be part of the Museum's forthcoming "Minding the Store" exhibit, slated to open in early 2011.

What businesses operated out of 97 Orchard Street over the years? How do you know?

The Museum's researchers use many different sources to find out about the history of our tenement building. City directory records, newspapers, factory inspector reports, and oral histories are just a few of the resources available to us when researching retail or manufacturing businesses.

For instance, the 1917 city directory records the following businesses occupying the storefronts spaces of 97 Orchard Street:

- Claman Stove Repair (Morris and Irving Claman)

- Orchard Printing Co.

- The dry goods store of Louis Schocken

- The watchmaking shop of Louis Rudow

1929:

Fisher, Harry Hosiery

Fischer & Schimmel Hosiery

Orchard Printing Co.

Scher, A. General Merchandise

Schimmel, Rubin Hosiery

Solomon, L Printer

1930:

Fischer & Schimmel Hosiery

Scher, A. General Merchandise

1931:

Reliable Jobbing Co.

S & D Underwear Corp.

Scher, A. General Merchandise

1933

S & D Underwear Corp.

Scher Jobbing House

Scherm Wm Jobber

1934

Duberman, H. Handbags

Scher’s Jobbing House Inc.

Scher’s Jobbing House Inc.

Seaboard Impt. Co.

1935

Duberman, H. Handbags

Gips & Mendesohn Inc. Hosiery

Seaboard Impt. Co.

1937

Auction Exchange

Gips & Mendesohn Inc. Hosiery

1939

Brandies, Herman Auctioneer

Brandies & Marcus Merchandise

Gips & Mendesohn Inc. Hosiery

1940

Gips & Mendesohn Inc. Hosiery

Scher, Wm. Auction Outlet

Does anyone want to share what a "jobber" is? I bet some of you readers know. Or worked as a jobber even?

Some of these businesses, including the auction house, will be part of the Museum's forthcoming "Minding the Store" exhibit, slated to open in early 2011.

Friday, February 26, 2010

Questions for Curatorial: The Fate of Schneider's

Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions. Read yesterday's post first.

What happened to Schneider’s Saloon after Caroline Schneider died and John Schneider moved out of 97 Orchard Street in 1886?

A year after his wife Caroline died from tuberculosis, John Schneider moved across the street to 98 Orchard. His saloon, a business that had operated in one of the basement storefronts at 97 Orchard Street since 1864, appears to have been taken over by Austrian-born Henry Infeld. According to the 1880 Census, Henry Infeld, then 21 years old, lived with his parents at 198 East Broadway and worked as a “segar dealer.”

When John Schneider moved to 98 Orchard Street in 1886, he also appears to have opened another saloon in one of the building’s storefronts. Why would Schneider open another saloon directly across the street? Museum researchers are not yet certain, but it is possible that Schneider might have had a falling out with 97 Orchard Street’s new owner, William Morris, a German immigrant, who bought the building from Lucas Glockner in 1886 for $29,000.

Schneider appears to have operated a saloon at 98 Orchard Street until 1890. He died two years later from tuberculosis at the public hospital on Randall’s Island.

Monday, more on the other businesses that operated at 97 Orchard Street during the same period.

What happened to Schneider’s Saloon after Caroline Schneider died and John Schneider moved out of 97 Orchard Street in 1886?

A year after his wife Caroline died from tuberculosis, John Schneider moved across the street to 98 Orchard. His saloon, a business that had operated in one of the basement storefronts at 97 Orchard Street since 1864, appears to have been taken over by Austrian-born Henry Infeld. According to the 1880 Census, Henry Infeld, then 21 years old, lived with his parents at 198 East Broadway and worked as a “segar dealer.”

When John Schneider moved to 98 Orchard Street in 1886, he also appears to have opened another saloon in one of the building’s storefronts. Why would Schneider open another saloon directly across the street? Museum researchers are not yet certain, but it is possible that Schneider might have had a falling out with 97 Orchard Street’s new owner, William Morris, a German immigrant, who bought the building from Lucas Glockner in 1886 for $29,000.

Schneider appears to have operated a saloon at 98 Orchard Street until 1890. He died two years later from tuberculosis at the public hospital on Randall’s Island.

Monday, more on the other businesses that operated at 97 Orchard Street during the same period.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

Questions for Curatorial: Schneider’s Saloon & LES Drinking Life

Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions.

When did John Schneider’s Saloon operate at 97 Orchard Street? When did the saloon close?

Bavarian-born John Schneider operated a lager bier saloon in one of 97 Orchard's basement storefronts between 1864 and 1886.

Schneider would not have been alone in his business. In 1865, a sanitary inspector named Dr. J.T. Kennedy visited the neighborhood on behalf of the Citizen’s Association Council on Public Health and Hygiene and counted a total of 526 drinking establishments in the 10th ward alone.

Seven years later in 1872, the police department counted a total of 726 drinking establishments in the 10th police district, whose boundaries were roughly coterminous with the 10th ward.

In 1882, the block of Orchard Street between Delancey and Broome was occupied for a total of four separate German lager beer saloons, including Schneider’s: Mr. John Kneher operated a saloon at 98 Orchard Street; Mr. Gustav Reichenbach operated a saloon at 94 Orchard Street; and Mr. Dederick Speh operated a saloon at 111 Orchard Street.

The saloonkeeper’s wife played an integral role in the operation of such establishments, from preparing the free lunch in the morning to greeting customers during the afternoons and evenings. So when John’s wife Caroline died from tuberculosis on June 8, 1885, it had a devastating effect on the business. It's likely that Caroline’s passing caused John to close the saloon about a year later. Records indicate that he and his only child, Harry, moved across the street to 98 Orchard.

John and Harry appear to have lived at 98 Orchard Street until 1892, when they moved several blocks away to 175 Ludlow Street. During this time, John was also suffering from tuberculosis. He died from the disease on May 12, 1892 at the Randall’s Island Adult Hospital, a public institution administered by the city of New York.

On June 18th, 1892, guardianship over 14-year-old Harry Schneider was officially given to his uncle, George Schneider, also a local saloonkeeper, who at the time was living at 105 Ludlow Street.

Stop by tomorrow to read more about the saloon. Schneider's business will be recreated in the "Minding the Store" exhibit in 97 Orchard Street's basement, slated to open in early 2011.

When did John Schneider’s Saloon operate at 97 Orchard Street? When did the saloon close?

Bavarian-born John Schneider operated a lager bier saloon in one of 97 Orchard's basement storefronts between 1864 and 1886.

Schneider would not have been alone in his business. In 1865, a sanitary inspector named Dr. J.T. Kennedy visited the neighborhood on behalf of the Citizen’s Association Council on Public Health and Hygiene and counted a total of 526 drinking establishments in the 10th ward alone.

Seven years later in 1872, the police department counted a total of 726 drinking establishments in the 10th police district, whose boundaries were roughly coterminous with the 10th ward.

In 1882, the block of Orchard Street between Delancey and Broome was occupied for a total of four separate German lager beer saloons, including Schneider’s: Mr. John Kneher operated a saloon at 98 Orchard Street; Mr. Gustav Reichenbach operated a saloon at 94 Orchard Street; and Mr. Dederick Speh operated a saloon at 111 Orchard Street.

The saloonkeeper’s wife played an integral role in the operation of such establishments, from preparing the free lunch in the morning to greeting customers during the afternoons and evenings. So when John’s wife Caroline died from tuberculosis on June 8, 1885, it had a devastating effect on the business. It's likely that Caroline’s passing caused John to close the saloon about a year later. Records indicate that he and his only child, Harry, moved across the street to 98 Orchard.

John and Harry appear to have lived at 98 Orchard Street until 1892, when they moved several blocks away to 175 Ludlow Street. During this time, John was also suffering from tuberculosis. He died from the disease on May 12, 1892 at the Randall’s Island Adult Hospital, a public institution administered by the city of New York.

On June 18th, 1892, guardianship over 14-year-old Harry Schneider was officially given to his uncle, George Schneider, also a local saloonkeeper, who at the time was living at 105 Ludlow Street.

Stop by tomorrow to read more about the saloon. Schneider's business will be recreated in the "Minding the Store" exhibit in 97 Orchard Street's basement, slated to open in early 2011.

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

A Little History of 75 Essex Street

Hello all! It’s Allison Siegel, Tenement Museum educator. In the upcoming months I’ll be writing some posts for the blog on neighborhood history stuff. First up is a mini neighborhood landmark!

Hello all! It’s Allison Siegel, Tenement Museum educator. In the upcoming months I’ll be writing some posts for the blog on neighborhood history stuff. First up is a mini neighborhood landmark!Not too far from our lady of Orchard Street is another relic of a bygone era. At the corner of Essex and Broome Streets stands 75 Essex Street (left), once home to the Eastern Dispensary.

A little background on dispensaries is required, so please allow me to tell you about the Eastern Dispensary’s sister, the Northern Dispensary in Greenwich Village (right). You may know it as the place where that somewhat famous writer, Edgar Allen Poe, once stayed as a patient. Founded in 1829, the Northern Dispensary is the only building in New York City with one side on two streets – Christopher and Grove Streets – and two sides on one street – Waverly Place.

Both the Eastern and Northern Dispensaries are freestanding buildings, which are pretty rare in our fine city of party walls and few alleyways.

But back to the Lower East Side:

The Eastern Dispensary (also known, by the late 19th century, as the Good Samaritan Dispensary) opened in 1832 and was built to provide the sick and poor with a place to receive aide and medicine. Helen Campbell, a 19th century missionary, described its patients in her 1898 book Darkness and Light; or, Lights and Shadows of New York Life:

Weary mothers with sick and wailing babies in their arms; women with bandaged heads and men with arms in slings; children sent by sick fathers and mothers at home for needed medicine. On most is the unmistakable look that tells of patient suffering and half-starved lives. . . .

Other publications focused on promoting the Dispensary’s success in aiding New York’s impoverished:

The dispensary is open daily, and furnishes gratuitous medical and surgical aid to the destitute sick of the eastern portion of the city. It also gives special attention to vaccination, which is freely performed upon all who apply for it, without respect to their station or pecuniary circumstances. Those able to pay for this service are invited to, and it is stated, generally do contribute to the funds of the institution.

Since its opening, it has aided seven hundred and sixty-four thousand persons, at an average cost, of fifteen cents each. The number treated the past year was twenty-six thousand two hundred and eighty-six…

The institution was visited June 4th [1870], and its operations observed.... The medical staff consists of a house physician and full boards of visiting and attending physicians and surgeons, the latter serving without pay. It is a well ordered and finely managed medical charity, worthy the gifts of the benevolent and the aid it receives from the State. (The 1870 Annual Report of the Board of State Commissioners of Public Charities of the City of New York State Page 170)

Fifteen cents! Somebody get Obama on the phone. Actually, there are still many clinics around the city providing pay-as-you’re-able health care – the Community Healthcare Network's downtown health center on Essex has been serving the Lower East Side since 1971. It’s certainly the legacy of the 19th century dispensaries.

But the Dispensary provided more than just doctor care. Have any of you been on our Moore family tour? If so, you already know about the 19th-century contaminated milk epidemic and its fatal effects on infants. One of the city’s “milk laboratories,” which provided sanitary milk for infants, was located at 75 Essex Street. Read yesterday’s post for more on that.

The Good Samaritan Dispensary closed in 1955. The New York City Register shows that on April 25, 1977, the City foreclosed on 75 Essex Street due to unpaid taxes. Cue the Eisner Brothers!

Shalom Eisner grew up in Williamsburg and rented the first floor space of 75 Essex Street in 1977. It was there that he opened the Eisner Brothers Store. They sell everything! Here’s a blurb from their website:

Our tremendous selection includes tee shirts, sweat-shirts, golf shirts, jackets, caps and hats… [we’re] the haven for uniformed officers; they know they can count on us for all their wardrobe needs.

Professional sports buffs and amateur wannabes: you won't find a better array of boxing equipment and licensed sports products than this.

Our collection of "I Love New York" items is beyond compare: creative, original and stimulating.

By 1985, Shalom Eisner and his family purchased the entire building. They’ve been in business for over thirty years. In this internet age, they’ve also been pretty successful with online sales.

Last year, 75 Essex Street was placed on the market for a cool $18 million. I had to know why, so I called the store and spoke with Shalom. He cited the recession as the reason why he decided to try to sell. (May I just add: People. Eisner Brothers is a neighborhood institution. GO SHOP THERE!)

While gushing over the 20 ft ceilings on every floor and the 14 ft-high ceiling in the basement, Shalom told me it’s his dream that if he sells the building “it will be left as is on the outside and become a single-family home for a famous person… Someone like Madonna. She could have her own Lower East Side home.”

He emphasized that whoever (in case Madonna isn’t interested) purchases 75 Essex Street will have to leave the outside as is (“that will be set forth in the contract”). So, not to fear, Lower East Siders and friends of preservation – while the Eastern Dispensary and its patients are long gone and Shalom and his brothers are on their way out, I can say with certainty that although Shalom believes there’s “potential for a swimming pool in the rear yard,” 75 Essex Street is going to stand strong for another 180 years.

Peace and Blessings until next time,

- Allison B. Siegel

Allison is an educator at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, self-proclaimed (and some other folks think so, too) 19th/20th century local historian and preservationist-in-training.

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

The Begecher Family History, Part 3

The story of the Begecher Family, who lived at 103 Orchard Street in the early 20th century, continues below. Read parts one and two. Research and writing by Alan Kurtz. Special thanks to Bowery Boogie.

On December 14th of 1904, five years after his arrival (the minimum time required by law), Marcus became an American citizen, taking the oath at the United States Eastern District Court. His Petition for Naturalization described him as a peddler living at 103 Orchard Street and noted that he could not read or write English but could “read and write the Hebrew language intelligently.” It wasn’t until 1906 that prospective citizens were required to know English.

Though much of the 1905 New York State Census has been lost, a hand-copied facsimile dating to the 1940s records the family as Max, Sarah, Ida, Lena, Rosa, Mendel, Sam, and Jackel Bulchecher. Max listed his occupation as peddler, Ida and Lena worked in “ladies wear,” while Sam and Jackel attended elementary school. Rosa and Mandel’s given occupations are not legible.

Five years later, at the time of the 1910 Federal Census, the family still resided on Orchard Street and were enumerated on April 16th under the names Marcus, Sabra, Ida, Max, Rose, Samuel, and Jacob Buchacher. Lilly was living elsewhere. Marcus was recorded as a salesman in a dry goods store, Ida and Rose as operators in a tailor shop, Max as a truck driver, and Sam an office boy. Unfortunately, their apartment number was not recorded. Whether Marcus, Ida, and Rose were still working for their more well-off Bralower relations is not known.

Two months later, on June 8, 1910 Ida Buchesser, age 23, married Max Katz, a 30 year old widower with a young son, and moved to the far reaches of the Bronx.

At some juncture during the early to mid 1910s, possibly when the building underwent extensive renovation in 1913, the family moved from 103 Orchard Street around the corner to 247 Broome Street. The family surname continued to evolve: Sam would retain the name Begecher, Max and Lilly would adopt the name Schesser, while Jack would somehow morph into Jack Schwartz.

Marcus and Sarah died within one year of each other: Marcus on May 22, 1923 and Sarah on May 12, 1924. They are buried in Acacia Cemetery in Ozone Park, Queens. Though their Death Certificates carry the surname of "Schesser," their headstones are inscribed "Betchesser."

Ida Begecher Katz died on January 24, 1961, having outlived her husband Max by almost 28 years.

Eventually all surviving family members would leave the Lower East Side.

My wife is the granddaughter of Ida Begecher Katz and great-granddaughter of Marcus and Sarah Begecher.

Do you have any information about 103 or 97 Orchard Street? Any memories of the people who lived there? Share them with us! Email press-inquiry (at) tenement . org.

- Posted by Kate

On December 14th of 1904, five years after his arrival (the minimum time required by law), Marcus became an American citizen, taking the oath at the United States Eastern District Court. His Petition for Naturalization described him as a peddler living at 103 Orchard Street and noted that he could not read or write English but could “read and write the Hebrew language intelligently.” It wasn’t until 1906 that prospective citizens were required to know English.

Marcus Begecher’s Petition for Naturalization: his address is 103 Orchard Street

Though much of the 1905 New York State Census has been lost, a hand-copied facsimile dating to the 1940s records the family as Max, Sarah, Ida, Lena, Rosa, Mendel, Sam, and Jackel Bulchecher. Max listed his occupation as peddler, Ida and Lena worked in “ladies wear,” while Sam and Jackel attended elementary school. Rosa and Mandel’s given occupations are not legible.

Five years later, at the time of the 1910 Federal Census, the family still resided on Orchard Street and were enumerated on April 16th under the names Marcus, Sabra, Ida, Max, Rose, Samuel, and Jacob Buchacher. Lilly was living elsewhere. Marcus was recorded as a salesman in a dry goods store, Ida and Rose as operators in a tailor shop, Max as a truck driver, and Sam an office boy. Unfortunately, their apartment number was not recorded. Whether Marcus, Ida, and Rose were still working for their more well-off Bralower relations is not known.

1910 Federal Census record for 103 Orchard Street; the family is listed in the middle.

Two months later, on June 8, 1910 Ida Buchesser, age 23, married Max Katz, a 30 year old widower with a young son, and moved to the far reaches of the Bronx.

At some juncture during the early to mid 1910s, possibly when the building underwent extensive renovation in 1913, the family moved from 103 Orchard Street around the corner to 247 Broome Street. The family surname continued to evolve: Sam would retain the name Begecher, Max and Lilly would adopt the name Schesser, while Jack would somehow morph into Jack Schwartz.

Jack and Lilly

Marcus and Sarah died within one year of each other: Marcus on May 22, 1923 and Sarah on May 12, 1924. They are buried in Acacia Cemetery in Ozone Park, Queens. Though their Death Certificates carry the surname of "Schesser," their headstones are inscribed "Betchesser."

Ida Begecher Katz died on January 24, 1961, having outlived her husband Max by almost 28 years.

Eventually all surviving family members would leave the Lower East Side.

My wife is the granddaughter of Ida Begecher Katz and great-granddaughter of Marcus and Sarah Begecher.

Do you have any information about 103 or 97 Orchard Street? Any memories of the people who lived there? Share them with us! Email press-inquiry (at) tenement . org.

- Posted by Kate

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

The Begecher Family History, Continued

The story of the Begecher Family, who lived at 103 Orchard Street in the early 20th century, continues below. Read part one here. Research and writing by Alan Kurtz. Special thanks to Bowery Boogie.

On July 9, 1899 Ida and Lilly’s father, listed on the steamship Friesland’s manifest as "Markus Boczezcer," a 54-year-old laborer, arrived from Antwerp, Belgium with one dollar to his name. Though quite young, Ida (and perhaps Lilly) had apparently saved enough money to at least contribute to the cost of his ticket.

He was briefly detained at the Barge Office at the Battery, most likely because immigration officials feared that he wouldn't be able to earn a living and thus become a “Public Charge.” (He came through the Battery because the original buildings at Ellis Island burned down in 1897, and the new brick buildings were still under construction at this time.)

Markus was probably released under the aegis of his brother-in-law Louis. Just nine days after his arrival, Marcus Begecher filed his Declaration of Intention (commonly called “First Papers” as they constituted the first step in the naturalization process) with the Southern District Circuit Court of the United States to become an American citizen: certainly a statement of commitment to his new and adopted country.

It would be three long years before the family was entirely reunited. Sarah, Mendel, Ruchel, Schema, and Snerza (Mendel would eventually become Max, Ruchel Rose, Schema Sam, and Schnerza Jack) arrived on the steamship La Bretagne sailing from Le Havre, France on September 7, 1902. The New York Times reported the weather as "cloudy; warmer; showers; southeast winds.”

The manifest records them as the "Bucecer" family. They were briefly detained at Ellis Island before Marcus arrived and obtained their release; La Bretagne had docked shortly after daybreak and the family was released at 2:35 in the afternoon. During their time in “detention” the family consumed five meals; one for each family member.

Sarah was not only reunited with her brother, Louis; her husband; and her two eldest daughters but also with additional siblings and her aged mother, Anyavita Bralower, who had come to America sometime during the 1890s.

Though it seems as if the family initially shared crowded living space with the Bralower family (Sarah's relations) on Hester Street, they soon moved to Eldridge Street (near Delancey Street) before relocating to 103 Orchard Street sometime before December of 1904.

...To be continued tomorrow, as the family makes a home on the Lower East Side.

- Posted by Kate

On July 9, 1899 Ida and Lilly’s father, listed on the steamship Friesland’s manifest as "Markus Boczezcer," a 54-year-old laborer, arrived from Antwerp, Belgium with one dollar to his name. Though quite young, Ida (and perhaps Lilly) had apparently saved enough money to at least contribute to the cost of his ticket.

He was briefly detained at the Barge Office at the Battery, most likely because immigration officials feared that he wouldn't be able to earn a living and thus become a “Public Charge.” (He came through the Battery because the original buildings at Ellis Island burned down in 1897, and the new brick buildings were still under construction at this time.)

Markus was probably released under the aegis of his brother-in-law Louis. Just nine days after his arrival, Marcus Begecher filed his Declaration of Intention (commonly called “First Papers” as they constituted the first step in the naturalization process) with the Southern District Circuit Court of the United States to become an American citizen: certainly a statement of commitment to his new and adopted country.

It would be three long years before the family was entirely reunited. Sarah, Mendel, Ruchel, Schema, and Snerza (Mendel would eventually become Max, Ruchel Rose, Schema Sam, and Schnerza Jack) arrived on the steamship La Bretagne sailing from Le Havre, France on September 7, 1902. The New York Times reported the weather as "cloudy; warmer; showers; southeast winds.”

The manifest records them as the "Bucecer" family. They were briefly detained at Ellis Island before Marcus arrived and obtained their release; La Bretagne had docked shortly after daybreak and the family was released at 2:35 in the afternoon. During their time in “detention” the family consumed five meals; one for each family member.

Sarah Bralower Begecher

Sarah was not only reunited with her brother, Louis; her husband; and her two eldest daughters but also with additional siblings and her aged mother, Anyavita Bralower, who had come to America sometime during the 1890s.

Though it seems as if the family initially shared crowded living space with the Bralower family (Sarah's relations) on Hester Street, they soon moved to Eldridge Street (near Delancey Street) before relocating to 103 Orchard Street sometime before December of 1904.

...To be continued tomorrow, as the family makes a home on the Lower East Side.

- Posted by Kate

Monday, November 16, 2009

The Begechers of 103 Orchard Street

When you are in the research business, sometimes you get lucky and things just come to you. A genealogist working for the Museum back in the early 1990s was handed the wrong file at an archive, and inside - quite by accident - was a letter of support for 97 Orchard Street resident Nathalie Gumpertz's petition to declare her husband legally dead. This story now forms the basis of the Getting By tour.

Last week, out of the blue, Bowery Boogie sent me an email - a Mr. Allen Kurtz had read on that blog about the Tenement Museum's research into 103 Orchard Street and wrote in to say, "My wife's family lived in that building from 1904 to 1910." As if that weren't cool enough on its own, Mr. Kurtz then sent along an extensive family history, charting the Begechers' arrival in the United States and their path through 103 Orchard Street and beyond.

I'm very happy to share that history with you this week. What's wonderful is how typical this immigrant experience is... and yet so personal to this distinct family.

Special thanks to Bowery Boogie.

The Begechers of 103 Orchard Street

By Alan Kurtz

In many ways, the Begechers (Marcus, Sarah, and their six children, Chaya, Liebe, and Ruchel, Mendel, Schema, and Schnerza) were typical Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Originally from Botosani, a small city in what is today northeast Romania, they more likely than not came to the United States to escape a life severely limited by persecution, oppression, and grinding poverty.

Not able to afford passage for the family to depart for America as an intact unit, the Begechers arrived in dribs and drabs as if a human chain; one saving up hard earned dollars to purchase passage for the next. Consequently, family members were often separated for months if not years.

Though it cannot be proven with complete accuracy, Chaya (who would subsequently Americanize her name to Ida) was likely the first to arrive, possibly sometime in 1898. Because she was still a child, perhaps as young as eight years of age, she came to America not in steerage, but as a Second Class passenger.

As steamship lines were not required to record their “better heeled” First and Second Class passengers on official manifests until 1903, her exact arrival date is not known, and it may be that she didn’t arrive until 1901.

Similarly, the name of the person who accompanied her to America is a perplexing mystery. What is known is that the man, who Ida would describe later in life as either an agent or an “uncle,” was quite protective of her and would not let her go down to steerage to meet other young passengers. As a result, she had no one to play with. All the while, she suffered from seasickness.

Her passage was paid for by her aunt and uncle, Celia and Louis Bralower of 50-52 Hester Street, who owned a thriving dry goods business. Their company, established in the 1880s, would survive for nearly 100 years.

Immediately after arrival, Ida was put to work in their shop to pay off her passage. Ida’s sister Liebe, who would later change her name to Lilly, may have arrived shortly thereafter. Her arrival manifest has also not been located.

To be continued tomorrow... as the rest of the family arrives in America.

- posted by Kate

Last week, out of the blue, Bowery Boogie sent me an email - a Mr. Allen Kurtz had read on that blog about the Tenement Museum's research into 103 Orchard Street and wrote in to say, "My wife's family lived in that building from 1904 to 1910." As if that weren't cool enough on its own, Mr. Kurtz then sent along an extensive family history, charting the Begechers' arrival in the United States and their path through 103 Orchard Street and beyond.

I'm very happy to share that history with you this week. What's wonderful is how typical this immigrant experience is... and yet so personal to this distinct family.

Special thanks to Bowery Boogie.

The Begechers of 103 Orchard Street

By Alan Kurtz

In many ways, the Begechers (Marcus, Sarah, and their six children, Chaya, Liebe, and Ruchel, Mendel, Schema, and Schnerza) were typical Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Originally from Botosani, a small city in what is today northeast Romania, they more likely than not came to the United States to escape a life severely limited by persecution, oppression, and grinding poverty.

Not able to afford passage for the family to depart for America as an intact unit, the Begechers arrived in dribs and drabs as if a human chain; one saving up hard earned dollars to purchase passage for the next. Consequently, family members were often separated for months if not years.

Though it cannot be proven with complete accuracy, Chaya (who would subsequently Americanize her name to Ida) was likely the first to arrive, possibly sometime in 1898. Because she was still a child, perhaps as young as eight years of age, she came to America not in steerage, but as a Second Class passenger.

As steamship lines were not required to record their “better heeled” First and Second Class passengers on official manifests until 1903, her exact arrival date is not known, and it may be that she didn’t arrive until 1901.

Similarly, the name of the person who accompanied her to America is a perplexing mystery. What is known is that the man, who Ida would describe later in life as either an agent or an “uncle,” was quite protective of her and would not let her go down to steerage to meet other young passengers. As a result, she had no one to play with. All the while, she suffered from seasickness.

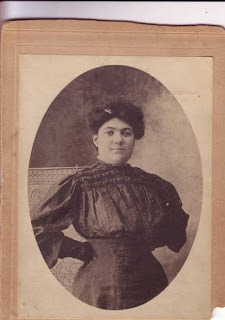

Ida Begecher Katz, later in life. Courtesy Alan Kurtz.

Her passage was paid for by her aunt and uncle, Celia and Louis Bralower of 50-52 Hester Street, who owned a thriving dry goods business. Their company, established in the 1880s, would survive for nearly 100 years.

Immediately after arrival, Ida was put to work in their shop to pay off her passage. Ida’s sister Liebe, who would later change her name to Lilly, may have arrived shortly thereafter. Her arrival manifest has also not been located.

To be continued tomorrow... as the rest of the family arrives in America.

- posted by Kate

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

Questions for Curatorial: The Significance of Bridges

Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions.

How did the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge affect people living on the Lower East Side?

The Brooklyn Bridge opened on May 24, 1883, instantly becoming the longest bridge in the world. As the first bridge connecting the cities of Brooklyn and New York (Manhattan), it offered a cheap alternative to the ferries that daily carried men back and forth between their homes and workplaces. It was also built largely by immigrant workers, many of whom lived on the Lower East Side.

When the Brooklyn Elevated to Fulton Ferry was completed in 1885, providing easy access to the interior of Brooklyn, traffic on the Bridge more than doubled, so that by 1885 it was handling some 20 million passengers a year.

For this reason, it undoubtedly aided the exodus of those immigrants and children of immigrants able to afford homes in Brooklyn and the daily commute by street car into the city. While the dispersal of the Lower East Side’s German and Irish immigrant communities was already well underway, the opening the Brooklyn bridge likely hastened their exodus.

But 25 years after it opened, the Lower East Side reached its peak population density.

Built in 1903, the Williamsburg Bridge had a greater effect on the ability of immigrants to leave the Lower East Side. In the early 20th century, the bridge was seen as a passageway to a new life in Williamsburg, Brooklyn by thousands of Jewish immigrants fleeing the overcrowded neighborhood.

Even more important was the inauguration of the subway in 1904, whose extension over the next several decades allowed for the further decentralization of the city by making rapid transportation accessible to the working-class New Yorker. Once subway lines had been extended to places like Brownsville and East New York in Brooklyn, these areas became second Lower East Sides — immigrant neighborhoods that provided homes, workplaces, and communities to thousands of new Americans.

(Images courtesy New York Public Library - United States in Stereo: In the Robert N. Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views; and United States History, Local History and Genealogy Division.)

How did the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge affect people living on the Lower East Side?

The Brooklyn Bridge opened on May 24, 1883, instantly becoming the longest bridge in the world. As the first bridge connecting the cities of Brooklyn and New York (Manhattan), it offered a cheap alternative to the ferries that daily carried men back and forth between their homes and workplaces. It was also built largely by immigrant workers, many of whom lived on the Lower East Side.

When the Brooklyn Elevated to Fulton Ferry was completed in 1885, providing easy access to the interior of Brooklyn, traffic on the Bridge more than doubled, so that by 1885 it was handling some 20 million passengers a year.

For this reason, it undoubtedly aided the exodus of those immigrants and children of immigrants able to afford homes in Brooklyn and the daily commute by street car into the city. While the dispersal of the Lower East Side’s German and Irish immigrant communities was already well underway, the opening the Brooklyn bridge likely hastened their exodus.

But 25 years after it opened, the Lower East Side reached its peak population density.

Built in 1903, the Williamsburg Bridge had a greater effect on the ability of immigrants to leave the Lower East Side. In the early 20th century, the bridge was seen as a passageway to a new life in Williamsburg, Brooklyn by thousands of Jewish immigrants fleeing the overcrowded neighborhood.

Even more important was the inauguration of the subway in 1904, whose extension over the next several decades allowed for the further decentralization of the city by making rapid transportation accessible to the working-class New Yorker. Once subway lines had been extended to places like Brownsville and East New York in Brooklyn, these areas became second Lower East Sides — immigrant neighborhoods that provided homes, workplaces, and communities to thousands of new Americans.

(Images courtesy New York Public Library - United States in Stereo: In the Robert N. Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views; and United States History, Local History and Genealogy Division.)

Wednesday, October 28, 2009

The Residential History of 103 Orchard Street

If you have followed along over the past week, you know that 103 Orchard Street, future Tenement Museum visitor center, was once three separate tenements, remodeled in 1916 into a single corner building. Here is a brief history of the some of the people who lived in those three buildings around the turn of the century.

The construction of 103, 105, and 107 Orchard coincided with the arrival of large numbers of Eastern-European immigrants to the Lower East Side. Most of the fifty-four families who inhabited these buildings from 1888 - 1900 hailed from the Jewish shtetls of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. The majority of them found work in New York’s burgeoning garment industry.

Taken two years after the tenements were erected, the 1890 Police Census represents the first comprehensive official record of their residents. The census documents occupancy by 247 individuals in fifty-four households ranging in size from three to nine people.

While union victories among garment industry workers were few during the 1890s, in 1894, the New York Times described a strike at Meyer Jonasson & Co.’s cloak-making factory on Grand Street. Meyer Jonasson & Co. was a very large garment producer, and during the 1890s the Times reports three separate strikes at their factories.

In the 1894 strike, about 500 workers gathered outside the factory, trying to block non-union replacement employees from going to work. The article states that the women in the crowd were “the worst fighters, and seriously attacked the police, scratching and kicking.” The police arrested one of these women, Mary Schumann of 107 Orchard Street, for slapping an officer in the face and throwing her baby at him when an arrest was attempted.

Already underway by 1890, the neighborhood’s population shift –- from German-speaking to Yiddish-speaking immigrants –- accelerated. A survey completed in 1901 by the United States Industrial Commission describes the changes in population on the Lower East Side:

According to the 1900 U.S. Census, a total of 269 individuals in 54 households called the tenements at 103, 105, and 107 Orchard Street home in that year. Slightly more than half of the heads of household were employed in the garment industry as tailors, cutters, cloak makers, and pants makers.

The large number of the remainder of heads-of-household were employed in similarly low-wage industries as peddlers and cigar makers. The buildings were also home to a musician, an auto maker, a plumber, two butchers, and a baker. Interestingly, a 103 Orchard Street resident was employed as a Rabbi, while his sons and daughters, ages ranging from 23 to 16, found work as cigar makers.

Through the first decade of the twentieth century, the demographic make-up of the all three tenements remained virtually unchanged. During the decade that witnessed the largest influx of immigrants in national history, the majority of their residents were eastern European garment workers.

(1) Reports of the Industrial Commission on Immigration and on Education (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901), 465, 469; quoted in Ford, Slums and Housing,183.

- Posted by Dave Favaloro, Research Manager

The construction of 103, 105, and 107 Orchard coincided with the arrival of large numbers of Eastern-European immigrants to the Lower East Side. Most of the fifty-four families who inhabited these buildings from 1888 - 1900 hailed from the Jewish shtetls of the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. The majority of them found work in New York’s burgeoning garment industry.

Taken two years after the tenements were erected, the 1890 Police Census represents the first comprehensive official record of their residents. The census documents occupancy by 247 individuals in fifty-four households ranging in size from three to nine people.

While union victories among garment industry workers were few during the 1890s, in 1894, the New York Times described a strike at Meyer Jonasson & Co.’s cloak-making factory on Grand Street. Meyer Jonasson & Co. was a very large garment producer, and during the 1890s the Times reports three separate strikes at their factories.

In the 1894 strike, about 500 workers gathered outside the factory, trying to block non-union replacement employees from going to work. The article states that the women in the crowd were “the worst fighters, and seriously attacked the police, scratching and kicking.” The police arrested one of these women, Mary Schumann of 107 Orchard Street, for slapping an officer in the face and throwing her baby at him when an arrest was attempted.

Already underway by 1890, the neighborhood’s population shift –- from German-speaking to Yiddish-speaking immigrants –- accelerated. A survey completed in 1901 by the United States Industrial Commission describes the changes in population on the Lower East Side:

The Hebrew population in the city, already dense in 1890, . . . has increased tremendously since then. . . . On the East Side they have extended their limits remarkably within the past 10 years[,] . . . driving the Germans before them, until it may be said that all of the East Side below Fourteenth street is a Jewish district. . . .The Germans did not like the proximity of the Jews, and so they left. (1)

According to the 1900 U.S. Census, a total of 269 individuals in 54 households called the tenements at 103, 105, and 107 Orchard Street home in that year. Slightly more than half of the heads of household were employed in the garment industry as tailors, cutters, cloak makers, and pants makers.

The large number of the remainder of heads-of-household were employed in similarly low-wage industries as peddlers and cigar makers. The buildings were also home to a musician, an auto maker, a plumber, two butchers, and a baker. Interestingly, a 103 Orchard Street resident was employed as a Rabbi, while his sons and daughters, ages ranging from 23 to 16, found work as cigar makers.

Through the first decade of the twentieth century, the demographic make-up of the all three tenements remained virtually unchanged. During the decade that witnessed the largest influx of immigrants in national history, the majority of their residents were eastern European garment workers.

(1) Reports of the Industrial Commission on Immigration and on Education (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901), 465, 469; quoted in Ford, Slums and Housing,183.

- Posted by Dave Favaloro, Research Manager

Monday, October 19, 2009

Schmatta: Rags to Riches to Rags

Tonight HBO will be broadcasting a new documentary called "Schmatta: Rags To Riches To Rags." While the film tells the story of the rise of New York's Garment District, it will also be focusing on its decline. The garment industry, which had once been a microcosm of economic and social forces, is now on the verge of disappearing. For instance, in 1965 the U.S. manufactured 95% of America's clothing. Today that number is down to 5%.

In case you would like to read more or watch the preview, see:

http://www.hbo.com/docs/programs/schmatta/index.html

- Posted by Rachel

In case you would like to read more or watch the preview, see:

http://www.hbo.com/docs/programs/schmatta/index.html

- Posted by Rachel

Labels:

Garment District,

lower east side history,

Media

Friday, October 16, 2009

History of 103 Orchard Street

Standing across the street from the corner tenement at 103 Orchard today, there is little evidence suggestive of the immense changes it has undergone since it was erected in the late 19th century. In 1888, the wood-frame dwellings at 103, 105, and 107 Orchard were replaced by three separate, individual dumbbell tenements, each 25 feet wide by 88.6 feet deep, each with 18 individual apartments.

Commissioned by Michael Fay and William Stacom, and constructed by architects Rentz and Lange for the sum of $25,000, these three tenements were built according to requirements of the 1879 Tenement House Act, known also as the “old law.”

The light and air requirements of the Act were physically manifested in the form of the dumbbell tenement, with its characteristic airshaft. Though the new design was intended to ameliorate the dark, dank interior rooms of pre-old law tenements (like 97 Orchard), they too soon became burdened with their own problems. Just eight years after being built, 105 Orchard Street was mentioned in a September 1895 New York Times article as a building the Board of Health would forcibly vacate if “not put in better sanitary condition within five days.”

The light and air requirements of the Act were physically manifested in the form of the dumbbell tenement, with its characteristic airshaft. Though the new design was intended to ameliorate the dark, dank interior rooms of pre-old law tenements (like 97 Orchard), they too soon became burdened with their own problems. Just eight years after being built, 105 Orchard Street was mentioned in a September 1895 New York Times article as a building the Board of Health would forcibly vacate if “not put in better sanitary condition within five days.”

In 1903, Delancey Street was widened as an approach to the newly built Williamsburg Bridge. In this widening, the tenements at 109, 111, and 113 Orchard Streets were demolished and cleared. The corner building at 83 Delancey Street was cleared as well. For about three years, the Delancey Street end of the block probably looked as if something was missing—the end of the street just shorn off. In 1906, the tenements at 103, 105, and 107 Orchard Street were purchased by Joseph Marcus, founder and president of the Bank of the United States. He completed major alterations that turned 107 Orchard into a corner building. Total cost: about $10,000.

The 1906 alteration was only the first of a series of changes that occurred at 103, 105, and 107 Orchard during the first decades of the 20th century. Undoubtedly the most far-reaching of these occurred in 1913. According to this Tenement House Department “Application to Alter a Tenement House,” 103, 105, and 107 Orchard were combined to create one building.

The description of alterations reads, “Rear part of all the buildings and southerly building to be removed; lots to be reapportioned and buildings altered so as to make one corner building. All stairs to be removed and new fireproof stairs erected. Partitions to be altered and bathrooms installed.”

The description of alterations reads, “Rear part of all the buildings and southerly building to be removed; lots to be reapportioned and buildings altered so as to make one corner building. All stairs to be removed and new fireproof stairs erected. Partitions to be altered and bathrooms installed.”

Before completion, these major alterations were met with some concern by the Tenement House Department. In this series of memoranda from July 1913, Acting Commissioner Abbot notes his opinion that “the three original buildings have been so changed in form, occupancy and location that the portion of the structure remaining when alterations are completed constituted so different a type of structure that existed originally that I feel the Department would have to treat the alteration of such a gigantic nature requiring the filing of the application form for a new law tenement…”

The old dumbbell tenements were altered to create one, single new law tenement. While each of the original buildings had 18 apartments, for a total of 54, the new building at 103 Orchard Street had a total of only 16 individual apartments, or four apartments on each of the second, third, fourth, and fifth floors. No residential units existed on the first or ground floor after 1913, as this level was dedicated commercial space. Sometime between 1913 and 1917, one apartment on the second floor was turned into a dentist’s office. In 1938, another apartment on the second floor was discontinued and used for storage. From 1938 to the present, 103 Orchard Street has had a total of 14 individual residential apartments.

103 Orchard Street photo courtesy Municipal Archives.

Commissioned by Michael Fay and William Stacom, and constructed by architects Rentz and Lange for the sum of $25,000, these three tenements were built according to requirements of the 1879 Tenement House Act, known also as the “old law.”

The light and air requirements of the Act were physically manifested in the form of the dumbbell tenement, with its characteristic airshaft. Though the new design was intended to ameliorate the dark, dank interior rooms of pre-old law tenements (like 97 Orchard), they too soon became burdened with their own problems. Just eight years after being built, 105 Orchard Street was mentioned in a September 1895 New York Times article as a building the Board of Health would forcibly vacate if “not put in better sanitary condition within five days.”

The light and air requirements of the Act were physically manifested in the form of the dumbbell tenement, with its characteristic airshaft. Though the new design was intended to ameliorate the dark, dank interior rooms of pre-old law tenements (like 97 Orchard), they too soon became burdened with their own problems. Just eight years after being built, 105 Orchard Street was mentioned in a September 1895 New York Times article as a building the Board of Health would forcibly vacate if “not put in better sanitary condition within five days.” In 1903, Delancey Street was widened as an approach to the newly built Williamsburg Bridge. In this widening, the tenements at 109, 111, and 113 Orchard Streets were demolished and cleared. The corner building at 83 Delancey Street was cleared as well. For about three years, the Delancey Street end of the block probably looked as if something was missing—the end of the street just shorn off. In 1906, the tenements at 103, 105, and 107 Orchard Street were purchased by Joseph Marcus, founder and president of the Bank of the United States. He completed major alterations that turned 107 Orchard into a corner building. Total cost: about $10,000.

The 1906 alteration was only the first of a series of changes that occurred at 103, 105, and 107 Orchard during the first decades of the 20th century. Undoubtedly the most far-reaching of these occurred in 1913. According to this Tenement House Department “Application to Alter a Tenement House,” 103, 105, and 107 Orchard were combined to create one building.

The description of alterations reads, “Rear part of all the buildings and southerly building to be removed; lots to be reapportioned and buildings altered so as to make one corner building. All stairs to be removed and new fireproof stairs erected. Partitions to be altered and bathrooms installed.”

The description of alterations reads, “Rear part of all the buildings and southerly building to be removed; lots to be reapportioned and buildings altered so as to make one corner building. All stairs to be removed and new fireproof stairs erected. Partitions to be altered and bathrooms installed.” Before completion, these major alterations were met with some concern by the Tenement House Department. In this series of memoranda from July 1913, Acting Commissioner Abbot notes his opinion that “the three original buildings have been so changed in form, occupancy and location that the portion of the structure remaining when alterations are completed constituted so different a type of structure that existed originally that I feel the Department would have to treat the alteration of such a gigantic nature requiring the filing of the application form for a new law tenement…”

The old dumbbell tenements were altered to create one, single new law tenement. While each of the original buildings had 18 apartments, for a total of 54, the new building at 103 Orchard Street had a total of only 16 individual apartments, or four apartments on each of the second, third, fourth, and fifth floors. No residential units existed on the first or ground floor after 1913, as this level was dedicated commercial space. Sometime between 1913 and 1917, one apartment on the second floor was turned into a dentist’s office. In 1938, another apartment on the second floor was discontinued and used for storage. From 1938 to the present, 103 Orchard Street has had a total of 14 individual residential apartments.

103 Orchard Street photo courtesy Municipal Archives.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)