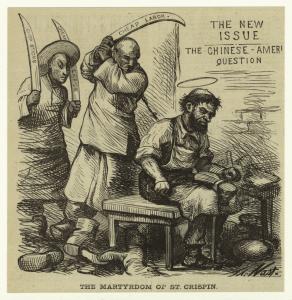

Courtesy New York Public Library, Mid-Manhattan Picture Collection.

This animosity toward the Chinese culminated in the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned Chinese laborers from entering the United States. Under the provisions of this act, the burden of proof for entry lay on the Chinese. The law also separated “desirable” and “undesirable” immigrants by including exceptions for merchants, students, teachers, and diplomats.

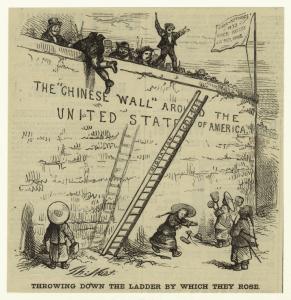

Courtesy New York Public Library, Mid-Manhattan Picture Collection. This Thomas Nast illustration was published in 1870. The anti-immigrant Know Nothing Party's flag is raised on the barricade.

The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first time that the United States passed a law to bar a specific race or ethnicity from entering the country. The immigration restrictions had important consequences for the character and experience of Chinese communities in America. During the period of exclusion, women and children were a rare sight in Chinatown “bachelor societies.”

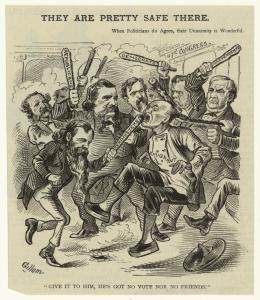

Courtesy New York Public Library, Mid-Manhattan Picture Collection. This 1882 illustration appeared in Puck magazine.

Initially, the act called for a ten-year period of exclusion, but exclusion lasted until after WWII when the 1943 Magnuson Act formally replaced exclusion with national quotas. The quota system still limited Chinese immigration to about 100 people per year so restrictions lasted in effect until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

Between 1881 and 1896, Chinese immigrants fought back by filing several lawsuits that went up to the Supreme Court. Many of these cases established precedents still used in human rights cases today.

- Special thanks to Beatrice Chen, Director of Education and Programs at the Museum of the Chinese in America, for writing this post. Visit MOCA to learn more about the Chinese immigrant experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.