Friday, April 30, 2010

Thursday, April 29, 2010

Poem in Your Pocket Day

Today we’ll be handing out copies of our favorite poems, including this classic:

We Real Cool

By Gwendolyn Brooks

THE POOL PLAYERS.

SEVEN AT THE GOLDEN SHOVEL.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

So why did we choose today to celebrate National Poetry Month? Thursday, April 29th is Poem in Your Pocket Day. The idea is to bring poetry into our everyday lives by carrying one of your favorite poems with you to share with others. And couldn’t we all use a little more poetry?

Poem in Your Pocket day has been celebrated in New York City since 2002. For a list of poetry-inspired events throughout the city, check out: http://www.nyc.gov/html/poem/html/home/home.shtml.

Come by to read the rest of our favorites and share yours with us! While you’re here, browse our poetry selections, including I Speak of the City and Beat Poets. You can even pick up a copy of Poem in Your Pocket and carry poetry with you every day.

I’ll leave you with one more selection of verse to ponder as the weather tries to decide which way to turn.

Spring III

By Audre Lorde

Spring is the harshest

Blurring the lines of choice

Until summer flesh

Swallows up all decision.

I remember after the harvest was over

When the thick sheaves were gone

And the bones of the gaunt trees

Uncovered

How the dying of autumn was too easy

To solve our loving.

- Posted by Kat Broadway

We Real Cool

By Gwendolyn Brooks

THE POOL PLAYERS.

SEVEN AT THE GOLDEN SHOVEL.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

So why did we choose today to celebrate National Poetry Month? Thursday, April 29th is Poem in Your Pocket Day. The idea is to bring poetry into our everyday lives by carrying one of your favorite poems with you to share with others. And couldn’t we all use a little more poetry?

Poem in Your Pocket day has been celebrated in New York City since 2002. For a list of poetry-inspired events throughout the city, check out: http://www.nyc.gov/html/poem/html/home/home.shtml.

Come by to read the rest of our favorites and share yours with us! While you’re here, browse our poetry selections, including I Speak of the City and Beat Poets. You can even pick up a copy of Poem in Your Pocket and carry poetry with you every day.

I’ll leave you with one more selection of verse to ponder as the weather tries to decide which way to turn.

Spring III

By Audre Lorde

Spring is the harshest

Blurring the lines of choice

Until summer flesh

Swallows up all decision.

I remember after the harvest was over

When the thick sheaves were gone

And the bones of the gaunt trees

Uncovered

How the dying of autumn was too easy

To solve our loving.

- Posted by Kat Broadway

Wednesday, April 28, 2010

Thursday, April 22, 2010

Murder Most Foul!

Ellen Horan, author of 31 Bond Street: A Novel, joins us for a guest-blog. Ellen will be at Tenement Talks tonight, 6:30 pm, 108 Orchard Street.

I stumbled upon the ‘Bond Street Murder,’ the actual murder that is the subject matter for this novel, in a newspaper clipping in a bin at the Pageant Print Shop. It had an image of Manhattan’s Bond Street and mentioned a long-forgotten murder of a dentist in his townhouse on that leafy street. The etching accompanying the article certainly didn't look anything like the Bond Street that I knew, which for more than a century suffered neglect as a backwater of empty lots, small manufacturing lofts and automotive shops.

It turns out that in 1857 this was one of the most fashionable parts of town, filled with fine homes and mature trees. One writer said, “The lamps, gleaming amid the leaves, reminded one of Paris.” In the early 19th century, Bond Street was the epitome of fashion. It was New York’s top address, and living there were: a mayor of New York, the town’s most preeminent physician, the pastor of the wealthiest church, a senator of the United States, two representatives of Congress, an ex-secretary of the Treasury, a major general in the army, and prominent financiers.

Curious to learn more about how murder could take place in this most posh of districts, I dug in at the library.

When I went to look through microfilm of old newspapers, I found that this was not some obscure case but one that played out across the front pages of all the New York City dailies for nearly a year, trumpeted at the time as the crime of the century.

I named the book after the house where the murder took place, 31 Bond Street, because the building’s fate seemed to mirror that of its inhabitants.

The fine home owned by dentist Harvey Burdell became the scene of a Coroner’s inquest into his murder. The house was turned inside out as events unfolded. The man’s housemistress, Emma Cunningham, with whom he had a romantic involvement, had designs upon the property but never got her hands on it, as her plans were thwarted when she became the main suspect of the murder.

After the Civil War, Bond Street showed evidence of decline, until all the townhouses were derelict or destroyed by the 1920s and were replaced by manufacturing or commercial buildings. The families touched by 31 Bond Street too seemed to fall into death or despair.

Today, Bond Street is again experiencing a renaissance. The tall buildings hold residential lofts and the empty lots have been replaced with prime condos.

Bond Street has come full circle, but I am sure it still has secrets to tell. As a fiction writer, I can’t help but be intrigued by the possibilities.

Join me tonight to learn more about the ‘Bond Street Murder’ and why it so captivated 19th century New York.

Images: Courtesy NYPL and Ellen Horan.

I stumbled upon the ‘Bond Street Murder,’ the actual murder that is the subject matter for this novel, in a newspaper clipping in a bin at the Pageant Print Shop. It had an image of Manhattan’s Bond Street and mentioned a long-forgotten murder of a dentist in his townhouse on that leafy street. The etching accompanying the article certainly didn't look anything like the Bond Street that I knew, which for more than a century suffered neglect as a backwater of empty lots, small manufacturing lofts and automotive shops.

It turns out that in 1857 this was one of the most fashionable parts of town, filled with fine homes and mature trees. One writer said, “The lamps, gleaming amid the leaves, reminded one of Paris.” In the early 19th century, Bond Street was the epitome of fashion. It was New York’s top address, and living there were: a mayor of New York, the town’s most preeminent physician, the pastor of the wealthiest church, a senator of the United States, two representatives of Congress, an ex-secretary of the Treasury, a major general in the army, and prominent financiers.

Curious to learn more about how murder could take place in this most posh of districts, I dug in at the library.

When I went to look through microfilm of old newspapers, I found that this was not some obscure case but one that played out across the front pages of all the New York City dailies for nearly a year, trumpeted at the time as the crime of the century.

I named the book after the house where the murder took place, 31 Bond Street, because the building’s fate seemed to mirror that of its inhabitants.

The fine home owned by dentist Harvey Burdell became the scene of a Coroner’s inquest into his murder. The house was turned inside out as events unfolded. The man’s housemistress, Emma Cunningham, with whom he had a romantic involvement, had designs upon the property but never got her hands on it, as her plans were thwarted when she became the main suspect of the murder.

After the Civil War, Bond Street showed evidence of decline, until all the townhouses were derelict or destroyed by the 1920s and were replaced by manufacturing or commercial buildings. The families touched by 31 Bond Street too seemed to fall into death or despair.

Today, Bond Street is again experiencing a renaissance. The tall buildings hold residential lofts and the empty lots have been replaced with prime condos.

Bond Street has come full circle, but I am sure it still has secrets to tell. As a fiction writer, I can’t help but be intrigued by the possibilities.

Join me tonight to learn more about the ‘Bond Street Murder’ and why it so captivated 19th century New York.

Images: Courtesy NYPL and Ellen Horan.

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

A Musical History

Head over to Bowery Boogie to read our post on an artifact - a piece of sheet music - found on the 4th floor of 97 Orchard Street during the 2007-2008 stabalization. Some commenters have already helped fill in the blanks about the songwriting team behind "I'm Marching Home to You," the song on the sheet music.

Click here to be taken to the post!

Click here to be taken to the post!

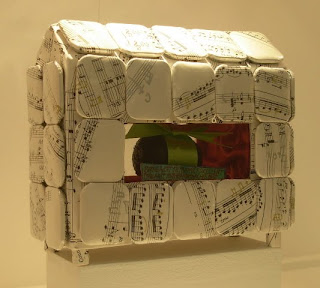

Tenement as Art?

A while back, we were approached by Irish artist Jennifer Walshe about working together on an art project. Jennifer's work is fairly complex and conceptual and so a bit hard to explain - read more in this Village Voice profile.

For an upcoming exhibit at the Chelsea Art Museum, she wanted to photograph small sculptures - what she calls "sound reliquaries" - in the rooms of the Moore family apartment. The reliquaries are created with different found objects, and in the middle of each is a bubble "containing" a sound from Ireland - ice cracking on the river, a voice telling stories by the fire.

At the exhibit are the reliquaries as well as photos of them in situ in the Moore apartment. With her work Jennifer is exploring traditional aspects of Irish culture in new ways.

The exhibit is up from April 15 - May 15, so stop by to check it out.

Chelsea Art Museum

556 West 22nd Street

Tuesday through Saturday 11am to 6pm

Thursday 11am to 8pm

Photos courtesy artist / Chelsea Art Museum

For an upcoming exhibit at the Chelsea Art Museum, she wanted to photograph small sculptures - what she calls "sound reliquaries" - in the rooms of the Moore family apartment. The reliquaries are created with different found objects, and in the middle of each is a bubble "containing" a sound from Ireland - ice cracking on the river, a voice telling stories by the fire.

At the exhibit are the reliquaries as well as photos of them in situ in the Moore apartment. With her work Jennifer is exploring traditional aspects of Irish culture in new ways.

The exhibit is up from April 15 - May 15, so stop by to check it out.

Chelsea Art Museum

556 West 22nd Street

Tuesday through Saturday 11am to 6pm

Thursday 11am to 8pm

Photos courtesy artist / Chelsea Art Museum

Labels:

Art,

art exhibit,

Ireland,

Irish,

Moore Family

Tuesday, April 20, 2010

Books from the Museum Shop for Mother's Day

(Come in or call and mention this blog post for 10% off your Mother’s Day gifts!!)

Last night we were joined by Dave Isay and StoryCorps for the launch of Mom: A Celebration of Mothers from StoryCorps, a collection of some of their most poignant stories, culled from their over 30,000 interviews with everyday Americans. We had Dave Isay stay a little longer and sign a stack of this new book, which makes a great gift for Mom, so call and get one while they last.

This got us thinking about great books and gifts for Mother’s Day, which is right around the corner. We’ve got lots of other book selections for your mom, whether she’s into history, fiction, or even graffiti.

For foodie mamas who have followed the life of the legendary Ruth Reichl, we suggest the new paperback For You Mom, Finally or choose from one of our wide selection of New York cookbooks.

My mom won’t read anything but fiction, and I’m constantly bringing her books from our New York and immigrant fiction shelves. She’s loved everything from fast-paced historical fiction and mysteries like Dreamland by Kevin Baker or The Alienist by Caleb Carr to contemporary immigration narratives such as The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz and The History of Love by Nicole Krauss.

And if your mother saves her ticket stubs, try a different kind of book, the perennially popular Ticket Stub Diary. Mom can organize the mementos of her favorite plays, movies, and concerts in this cute little book.

No matter what your mother is into, we’ve got the perfect gift for her. No, seriously! We've got a little something for everyone. As an extra incentive, mention the blog when you make your purchase for 10% off your Mother’s Day gifts. Don't forget, buying something is like making a donation to the Tenement Museum. Every little bit helps.

Tenement Museum Shop

108 Orchard Street (Delancey)

212-982-8420

Monday-Sunday, 10am - 6pm

- Posted by Kat Broadway

Last night we were joined by Dave Isay and StoryCorps for the launch of Mom: A Celebration of Mothers from StoryCorps, a collection of some of their most poignant stories, culled from their over 30,000 interviews with everyday Americans. We had Dave Isay stay a little longer and sign a stack of this new book, which makes a great gift for Mom, so call and get one while they last.

This got us thinking about great books and gifts for Mother’s Day, which is right around the corner. We’ve got lots of other book selections for your mom, whether she’s into history, fiction, or even graffiti.

For foodie mamas who have followed the life of the legendary Ruth Reichl, we suggest the new paperback For You Mom, Finally or choose from one of our wide selection of New York cookbooks.

My mom won’t read anything but fiction, and I’m constantly bringing her books from our New York and immigrant fiction shelves. She’s loved everything from fast-paced historical fiction and mysteries like Dreamland by Kevin Baker or The Alienist by Caleb Carr to contemporary immigration narratives such as The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz and The History of Love by Nicole Krauss.

And if your mother saves her ticket stubs, try a different kind of book, the perennially popular Ticket Stub Diary. Mom can organize the mementos of her favorite plays, movies, and concerts in this cute little book.

No matter what your mother is into, we’ve got the perfect gift for her. No, seriously! We've got a little something for everyone. As an extra incentive, mention the blog when you make your purchase for 10% off your Mother’s Day gifts. Don't forget, buying something is like making a donation to the Tenement Museum. Every little bit helps.

Tenement Museum Shop

108 Orchard Street (Delancey)

212-982-8420

Monday-Sunday, 10am - 6pm

- Posted by Kat Broadway

Thursday, April 15, 2010

More IHW - Report from the Mayor's Breakfast

Today I was representing the Tenement Museum at a Gracie Mansion breakfast celebration kicking off 2010 NYC Immigrant Heritage Week. It was an honor and a pleasure to be around so many interesting people from New York City. I got to meet and take a photo with the Mayor and with the Commissioner of Immigrant Affairs from the Mayor’s Office.

The Tenement Museum and many colleagues from our neighborhood are participating in this week-long series of events commemorating the great immigrant heritage in the city of New York. Being at this celebration made me proud to be an immigrant and to work at an immigration museum. People were in good spirits and really excited to kick off the celebrations; the Mayor spoke briefly and shared a laugh with us while at the same time making a strong point about immigration.

Listening to the Mayor made me realize how important the voices of immigrants are. The Mayor encouraged all of us to fill out the census forms this year -- for many obvious reasons, of course -- but he spoke about how the census allows us to have more representation in Congress and in the New York State Assembly. More voices from places like NYC can help push forward reasonable immigration legislation for our country.

A city like New York has so many immigrants that our voices can weight more -- we can help everyone in the country understand the foundation immigrants have built here. The Mayor used this idea to express his feelings on how a country of immigrants should cherish its heritage and the influence of so many people from around the world who have made their homes here.

He encouraged us to be the ones to take the lead and be more involved. The simplest thing we can do it is fill out the census. That way, all of New York's many voices will be heard.

We can use this week to think about the influence immigrants had and still have in shaping the United States. This breakfast celebration really made look forward even more to the upcoming events this week. Of course, I celebrate my immigrant experience every day, but this week will be even more special.

- Posted by Pedro Garcia, Education Associate for Training & Outreach

The Tenement Museum and many colleagues from our neighborhood are participating in this week-long series of events commemorating the great immigrant heritage in the city of New York. Being at this celebration made me proud to be an immigrant and to work at an immigration museum. People were in good spirits and really excited to kick off the celebrations; the Mayor spoke briefly and shared a laugh with us while at the same time making a strong point about immigration.

Listening to the Mayor made me realize how important the voices of immigrants are. The Mayor encouraged all of us to fill out the census forms this year -- for many obvious reasons, of course -- but he spoke about how the census allows us to have more representation in Congress and in the New York State Assembly. More voices from places like NYC can help push forward reasonable immigration legislation for our country.

A city like New York has so many immigrants that our voices can weight more -- we can help everyone in the country understand the foundation immigrants have built here. The Mayor used this idea to express his feelings on how a country of immigrants should cherish its heritage and the influence of so many people from around the world who have made their homes here.

He encouraged us to be the ones to take the lead and be more involved. The simplest thing we can do it is fill out the census. That way, all of New York's many voices will be heard.

We can use this week to think about the influence immigrants had and still have in shaping the United States. This breakfast celebration really made look forward even more to the upcoming events this week. Of course, I celebrate my immigrant experience every day, but this week will be even more special.

- Posted by Pedro Garcia, Education Associate for Training & Outreach

It's Immigrant Heritage Week!

Each year, the Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs sponsors a week dedicated to recognizing the contributions of immigrants to our City. Different museums, cultural centers, settlement houses, dance companies, and other organizations host free or low-cost events that celebrate New York's vibrant heritage.

The Tenement Museum has been fortunate to be part of this event series since the beginning, and we've hosted a number of programs (most memorable, to me, was Crossing the BLVD).

This year, we're offering a FREE walking tour of the Lower East Side. Come by the Visitors Center & Museum Shop on Wednesday, April 21. The tour leaves at 2:30 PM, and tickets will be distributed starting at 10 AM. (Sorry, we're only able to give them out on the day of the program, and only two per person are allowed. The tour is capped at 25.)

The tour is the newest in the Museum's roster, focusing on the trends that shaped the neighborhood after 1935. So much happened here in the 20th century that we don't get into on our building tours. We'll be able to discuss gentrification and neighborhood change, immigration trends post-1966, how buildings have been changed and reused, and how urban renewal affected the Lower East Side in ways good and bad.

"Next Steps," as the tour is called, has its "soft launch" this month and next on the weekends (Saturday/Sunday at 2:30 PM), and by summer we'll be offering it daily, so feel free to come by another time if you can't make it during Immigrant Heritage Week. We also offer walking tours for private groups of 15 or more, which is a great option if you're looking for a discounted price and a personalized experience.

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention some of the other IHW events happening in the neighborhood.

- The Educational Alliance has a concert for kids featuring music from around the world. (All week)

- The Museum at Eldridge Street has a family scavenger hunt they're giving away if you stop by. (All week)

- The Museum of the Chinese in America is offering a walking tour of Chinatown. (All week, 10:30 AM)

- American Immigration Lawyers Association hosts a citizenship workshop for green card holders at PS 2, 122 Henry Street. (4/17, 11 AM - 3 PM)

- CSV Center has two plays and a film screening - a Loisaida Romeo & Juliet; a retelling of the food riots of 1917; and a documentary about those who've stayed behind while family members immigrate to the United States. (Various dates)

- Seward Park Library hosts the play Two Friends: Dos Amigos. (4/19, 6:30 - 7:30 PM)

- Italian American Museum hosts a lecture on the support Italian immigrants gave to the people of Sicily after a 1908 earthquake. (4/21, 6:30 - 7:30 PM)

- And last but not least, Immigrant Social Services has a photography project titled, "The Joys and Anguishes of Immigrants in the Lower East Side / Chinatown Community." (4/21, 4:00 - 6:00 PM)

We hope you'll make it out to one or more events over the next seven days and honor all those who have made, and are making their way, in New York City.

- posted by kate

Wednesday, April 14, 2010

See you at the Confetti Dance?

Educator Allison Siegel continues her research into buildings on the Lower East Side. At the request of curious Tenement Museum staffers, she looked into 345 Grand Street, a cast iron building at the corner of Ludlow.

My first attempt at researching 345 Grand Street brought me to an interesting blog called Coretalks.com. Click to read more, but in a nutshell, over the years the building was a dance hall and a piano showroom.

I was immediately obsessed with finding out more! Could this building have been all that was claimed?

I was able to confirm H.W. Perlman’s Piano outlet was there, but was unsuccessful locating when. After hours of research, I caved and contacted the author of the blog, David Grossman, who put me in touch with one of the previous owner of the building. Here’s what he had to say:

(I am working on continuing Mr. Frazer’s research of Little Willie and Big Sam Kaplan and The Confetti Dance- stay tuned for what I find!)

While Mr. Frazer couldn't specify years, he did provide me with a ton of additional info to research, and so I did…

Not only was there a dancehall at 345 Grand, but when the building opened between Dec. 2 and Dec. 8, 1888, it did so as a “combination museum, theatre, menagerie and aquarium” in 1888.

‘til next time.

-A. B. Siegel

Thanks to Coretalks.com for the images.

My first attempt at researching 345 Grand Street brought me to an interesting blog called Coretalks.com. Click to read more, but in a nutshell, over the years the building was a dance hall and a piano showroom.

I was immediately obsessed with finding out more! Could this building have been all that was claimed?

I was able to confirm H.W. Perlman’s Piano outlet was there, but was unsuccessful locating when. After hours of research, I caved and contacted the author of the blog, David Grossman, who put me in touch with one of the previous owner of the building. Here’s what he had to say:

Hello Allison,

David's article tells you most of what I know about the building. The exterior photo from around 1900 was retrieved from NY City archives by another owner, David Rakovsky on the 4th floor. When I was negotiating to buy the building in 1999, a man named Jimmy, who had been employed as a super by the owners Alan and Alice Friedman for many years, told me there used to be a dance parlor in the place, and with nods and winks he suggested that where there was dancing, there was probably a brothel too. I have no idea if that's true as a generalization, let alone true for 345 Grand.

In any event, the dance ticket we discovered under the floorboards confirms that the 2nd floor was a dance hall, and the stairway that used to connect the 1st and 2nd floors suggests that it might have occupied both floors -- perhaps a lounge or smoking room downstairs? We Googled the performers, Little Willie and Big Sam Kaplan, and contacted a few Kaplans with a LES background but learned nothing more. We surmise that a confetti dance had the band playing a medley -- a polka, a waltz, etc -- and there's an 1889 short film cited on Google called The Confetti Dance, but no information about it.

That's about all I know, except for a few half-credible stories about Lou Reid and Blondie having (at different times) lived next door or behind us, on Ludlow.

cheers

Phillip Frazer

(I am working on continuing Mr. Frazer’s research of Little Willie and Big Sam Kaplan and The Confetti Dance- stay tuned for what I find!)

While Mr. Frazer couldn't specify years, he did provide me with a ton of additional info to research, and so I did…

Not only was there a dancehall at 345 Grand, but when the building opened between Dec. 2 and Dec. 8, 1888, it did so as a “combination museum, theatre, menagerie and aquarium” in 1888.

“THE GRAND STREET MUSEUM A VERY humble east side place of amusement was THE GRAND STREET MUSEUM situated at Nos 345 and 347 Grand Street It was opened Dec 8 1888 and besides the living and other curiosities to be seen there dramatic performances were given and all could be enjoyed for ten cents.”

A history of the New York stage from the first performance in 1732 ..., Volume 2Yet another intriguing piece of New York City’s history, and folks, if you fancy yourself a new condo (FYI: according to the NY City Register, the building converted to the Grand Digs Condominium on April 8, 2003) -- some of the units are up for grabs.

By Thomas Allston Brown

Page 591

‘til next time.

-A. B. Siegel

Thanks to Coretalks.com for the images.

Labels:

building histories,

lower east side history,

Music

Tuesday, April 13, 2010

News from Around the Web

Seven-alarm fire on Grand Street late Sunday night. Apparently the building owners have been sited for multiple violations of housing codes in the last two years. From Fire Chief Kilduff: "Because the buildings are old - the two buildings here are 110 years old - there's an awful lot of voids and shafts in these buildings and the fire just travels all through the place." (These would be the air shafts meant to increase air circulation in the apartments.)

Reports have called this area both "Chinatown" and "the Lower East Side." Historic boundary of the LES = the Bowery.

[Bowery Boogie]

[Daily News]

From Darfur to Brooklyn - photographs of refugees who have settled in Kensington.

[New York Times]

Urban spelunker Steve Duncan gets to the heart of the City's infrastructure (and takes some cool photos of old sewers, too).

[Columbia Magazine]

T.J. Stiles, coming to Tenement Talks on May 14, wins the Pulitzer.

[Pulitzer.org]

Edited to add...

Lower East Side photos, in color, from the 1940s. Cool!!

[City Noise]

Reports have called this area both "Chinatown" and "the Lower East Side." Historic boundary of the LES = the Bowery.

[Bowery Boogie]

[Daily News]

From Darfur to Brooklyn - photographs of refugees who have settled in Kensington.

[New York Times]

Urban spelunker Steve Duncan gets to the heart of the City's infrastructure (and takes some cool photos of old sewers, too).

[Columbia Magazine]

T.J. Stiles, coming to Tenement Talks on May 14, wins the Pulitzer.

[Pulitzer.org]

Edited to add...

Lower East Side photos, in color, from the 1940s. Cool!!

[City Noise]

Thursday, April 8, 2010

Give us your Pulitzer picks

Booksellers and literary fans the world over anticipate the annual announcement of the Pulitzer Prizewinners, all the more so because the finalists are not revealed in advance.

What are your favorite picks from 2009?

Tell us your forecast for Pulitzer winners in Literature, History, and Journalism (one per category), and if you’re right, you’ll win a $5.00 gift certificate to the Museum Shop. Leave your guesses in the comments.

This year’s winners will be announced on Monday, April 12, at 3 pm, corresponding nicely with our Tenement Talk with James McGrath Morris, author of Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print, and Power (Monday, April 12, at 6:30 pm, 108 Orchard St, FREE).

And when you come in to pick up your gift certificate, consider putting it towards the purchase of a past Pulitzer winner.

Many of these distinguished titles are among our bestsellers, including The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York by Robert A. Caro, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon Reed, and Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace in non-fiction categories.

Some of our bestselling fiction and memoir titles have been past Pulitzer winners as well, including Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz, and The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon.

Stop by to check them out and for recommendations for further reading on New York history and literature. Don’t forget to send us your predictions for this year’s Pulitzer Prizewinners, and we look forward to seeing you at the Tenement Talk on Monday night.

- Posted by Kat Broadway

What are your favorite picks from 2009?

Tell us your forecast for Pulitzer winners in Literature, History, and Journalism (one per category), and if you’re right, you’ll win a $5.00 gift certificate to the Museum Shop. Leave your guesses in the comments.

This year’s winners will be announced on Monday, April 12, at 3 pm, corresponding nicely with our Tenement Talk with James McGrath Morris, author of Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print, and Power (Monday, April 12, at 6:30 pm, 108 Orchard St, FREE).

And when you come in to pick up your gift certificate, consider putting it towards the purchase of a past Pulitzer winner.

Many of these distinguished titles are among our bestsellers, including The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York by Robert A. Caro, The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon Reed, and Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace in non-fiction categories.

Some of our bestselling fiction and memoir titles have been past Pulitzer winners as well, including Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz, and The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon.

Stop by to check them out and for recommendations for further reading on New York history and literature. Don’t forget to send us your predictions for this year’s Pulitzer Prizewinners, and we look forward to seeing you at the Tenement Talk on Monday night.

- Posted by Kat Broadway

Wednesday, April 7, 2010

From Every End of This Earth

Today we're lucky to have Steven V. Roberts, author of From Every End of This Earth, guest-blogging for us. Steven will be at Tenement Talks on April 15. The book is a marvelous collection of immigrant stories, featuring 13 families from around the globe, who've all come to the US to work, raise families, and start new lives. As you will read below, Steven is deeply inspired by his own family's immigration story.

As I listened to Barack Obama’s inaugural address, I heard him say: “We are a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus, and nonbelievers. We are shaped by every language and culture, drawn from every end of this earth.”

I knew then that I had a title for this book. I liked the lilt of his language, but more than that, I shared his sense of what makes America great. This country’s genius flows from its diversity.

“We know,” said the new president, “that our patchwork heritage is a strength, not a weakness.”

Or as Eddie Kamara Stanley of Sierra Leone puts it, “it’s the nation of nations, you can see every nation in America.”

But diversity only describes color not character, ethnicity not ingenuity. Over many generations, the immigrants who chose to come here, and were strong enough to complete the journey, were the most ambitious, the most determined, the most resilient adventurers the Old World had to offer.

“The greatness of our nation…must be earned,” said the new president, and building that greatness has never been “for the faint-hearted.” Rather, he added, “it has been the risk-takers, the doers, the makers of things” who led the way.

“For us they packed up their few worldly possessions and traveled across oceans in search of a new life.”

The “faint-hearted” stayed behind.

This book is about the doers, the risk-takers, the makers of things that Obama describes. The president knows them well because his own father was an immigrant from Kenya, and his stepfather was from Indonesia.

I know them well, too. All four of my grandparents came from the “pale of settlement” on the Western edge of the Russian empire where Jews were allowed to settle in the 19th century. They were born between 1881 and 1892, and while they all described themselves as Russian, borders have shifted so often since then that their hometowns today are in three different countries - Poland, Belarus and Lithuania.

Both of my grandfathers were carpenters, “makers of things,” who settled in Bayonne, N.J., just across the Hudson River from Manhattan. One lived with us, in a house he had built himself, while my other grandparents were three blocks away.

I thought everybody grew up that way and most of my friends did. Our grandparents all had accents and our babysitters all were related. If our families weren’t Russian or Polish, they were Irish or Italian, with an occasional Czech or Ukrainian or Litvak thrown in. I grew up thinking WASPS were a tiny minority group.

Most of our relatives fled a life of poverty or persecution in the Old Country and would not talk about the past; they wanted to leave all that behind and become American.

But I was lucky: my Grandpa Abe used to tell me tales of his youth in Bialystok, a town that achieved a fleeting notoriety when Mel Brooks used the name “Max Bialystok” for the main character in his play The Producers.

In fact Abe, like many immigrants, moved more than once, and spent his teenage years as a Zionist pioneer in Palestine, working on the first roads ever built in what’s now Tel Aviv.

He arrived in America on April 7, 1914, aboard a ship called the George Washington that sailed from Bremen, a port on the North Sea. The manifest spells both of his names wrong (“Awram Rogowski” instead of “Avram Rogowsky”) and persistent mistakes like that have hampered the search for my family’s records. On her birth certificate, my mother is listed as “Dora Schaenbein”, when in fact her name was Dorothy Schanbam. At her 90th birthday party I took note of that discrepancy and joked that perhaps we were celebrating the wrong woman entirely.

This background left me with a life long interest in ethnicity and immigration. My last book, My Fathers’ Houses, chronicled my family’s arrival in the New World and the lives we made here. This book is really an update, the stories of 13 families who are living the journey today that Grandpa Abe and my other ancestors made almost 100 years ago.

In a sense I have been working on this volume for my entire writing life. When I became a reporter on the city staff of the New York Times in 1965, I convinced the editors to let me do a series about the ethnic neighborhoods of New York.

One favorite was Arthur Avenue, an old Italian section near the Bronx Zoo, and I remember coming back from that assignment with some great anecdotes and a box of delicious cannolis from a local bakery. On weekends my wife and I occasionally roamed the Lower East Side, and one favorite destination was Katz’s deli on Houston Street, started by Russian immigrants in 1888 and famous for its slogan, “Send a salami to your boy in the army!”

Some years later, when I decided to search for my own roots in Europe, I called the Bialystoker Center on East Broadway. They put me in touch with a man who was an expert on the Jews of Eastern Poland. With his help, my wife and I journeyed to Bialystok in 1991.

I asked to go to the train station, where many of Grandpa Abe’s early adventures had taken place. You’re in luck, said the guide, that’s one of the few buildings left in town that looks the way it did when your grandfather lived here.

As I walked out onto the platform, I could feel Abe’s spirit. I looked upward, held out my arms, and said softly, “Pop, we survived, and I’m here to prove it.” Then I broke down and wept, not realizing until that moment how deeply grateful I was to my grandparents for having the heart and heroism to make a new life for themselves and their grandson in a new land.

They are all heroes -- the generations who poured through the Lower East Side a hundred years ago and the ones who still come today, from every end of this earth.

- Steven V. Roberts

As I listened to Barack Obama’s inaugural address, I heard him say: “We are a nation of Christians and Muslims, Jews and Hindus, and nonbelievers. We are shaped by every language and culture, drawn from every end of this earth.”

I knew then that I had a title for this book. I liked the lilt of his language, but more than that, I shared his sense of what makes America great. This country’s genius flows from its diversity.

“We know,” said the new president, “that our patchwork heritage is a strength, not a weakness.”

Or as Eddie Kamara Stanley of Sierra Leone puts it, “it’s the nation of nations, you can see every nation in America.”

But diversity only describes color not character, ethnicity not ingenuity. Over many generations, the immigrants who chose to come here, and were strong enough to complete the journey, were the most ambitious, the most determined, the most resilient adventurers the Old World had to offer.

“The greatness of our nation…must be earned,” said the new president, and building that greatness has never been “for the faint-hearted.” Rather, he added, “it has been the risk-takers, the doers, the makers of things” who led the way.

“For us they packed up their few worldly possessions and traveled across oceans in search of a new life.”

The “faint-hearted” stayed behind.

This book is about the doers, the risk-takers, the makers of things that Obama describes. The president knows them well because his own father was an immigrant from Kenya, and his stepfather was from Indonesia.

I know them well, too. All four of my grandparents came from the “pale of settlement” on the Western edge of the Russian empire where Jews were allowed to settle in the 19th century. They were born between 1881 and 1892, and while they all described themselves as Russian, borders have shifted so often since then that their hometowns today are in three different countries - Poland, Belarus and Lithuania.

Both of my grandfathers were carpenters, “makers of things,” who settled in Bayonne, N.J., just across the Hudson River from Manhattan. One lived with us, in a house he had built himself, while my other grandparents were three blocks away.

I thought everybody grew up that way and most of my friends did. Our grandparents all had accents and our babysitters all were related. If our families weren’t Russian or Polish, they were Irish or Italian, with an occasional Czech or Ukrainian or Litvak thrown in. I grew up thinking WASPS were a tiny minority group.

Most of our relatives fled a life of poverty or persecution in the Old Country and would not talk about the past; they wanted to leave all that behind and become American.

But I was lucky: my Grandpa Abe used to tell me tales of his youth in Bialystok, a town that achieved a fleeting notoriety when Mel Brooks used the name “Max Bialystok” for the main character in his play The Producers.

In fact Abe, like many immigrants, moved more than once, and spent his teenage years as a Zionist pioneer in Palestine, working on the first roads ever built in what’s now Tel Aviv.

He arrived in America on April 7, 1914, aboard a ship called the George Washington that sailed from Bremen, a port on the North Sea. The manifest spells both of his names wrong (“Awram Rogowski” instead of “Avram Rogowsky”) and persistent mistakes like that have hampered the search for my family’s records. On her birth certificate, my mother is listed as “Dora Schaenbein”, when in fact her name was Dorothy Schanbam. At her 90th birthday party I took note of that discrepancy and joked that perhaps we were celebrating the wrong woman entirely.

This background left me with a life long interest in ethnicity and immigration. My last book, My Fathers’ Houses, chronicled my family’s arrival in the New World and the lives we made here. This book is really an update, the stories of 13 families who are living the journey today that Grandpa Abe and my other ancestors made almost 100 years ago.

In a sense I have been working on this volume for my entire writing life. When I became a reporter on the city staff of the New York Times in 1965, I convinced the editors to let me do a series about the ethnic neighborhoods of New York.

One favorite was Arthur Avenue, an old Italian section near the Bronx Zoo, and I remember coming back from that assignment with some great anecdotes and a box of delicious cannolis from a local bakery. On weekends my wife and I occasionally roamed the Lower East Side, and one favorite destination was Katz’s deli on Houston Street, started by Russian immigrants in 1888 and famous for its slogan, “Send a salami to your boy in the army!”

Some years later, when I decided to search for my own roots in Europe, I called the Bialystoker Center on East Broadway. They put me in touch with a man who was an expert on the Jews of Eastern Poland. With his help, my wife and I journeyed to Bialystok in 1991.

I asked to go to the train station, where many of Grandpa Abe’s early adventures had taken place. You’re in luck, said the guide, that’s one of the few buildings left in town that looks the way it did when your grandfather lived here.

As I walked out onto the platform, I could feel Abe’s spirit. I looked upward, held out my arms, and said softly, “Pop, we survived, and I’m here to prove it.” Then I broke down and wept, not realizing until that moment how deeply grateful I was to my grandparents for having the heart and heroism to make a new life for themselves and their grandson in a new land.

They are all heroes -- the generations who poured through the Lower East Side a hundred years ago and the ones who still come today, from every end of this earth.

- Steven V. Roberts

Tuesday, April 6, 2010

Another Poem of New York

In honor of National Poetry Month, here is another poem from the collection I Speak of the City: Poems of New York. This classic, written by Emma Lazarus in 1883, was inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty in 1903. The poem was written in support of a fund-raising campaign to build a pedestal for the now-famous statue.

The New Colossus

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her milk eyes command

The air-bridged barbor that twin cities frame.

"Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!' cries she

With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door."

The New Colossus

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her milk eyes command

The air-bridged barbor that twin cities frame.

"Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!' cries she

With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door."

Friday, April 2, 2010

“You Shall Not Oppress A Stranger”

My family just had its Passover seder, and after almost two years as a museum educator, I’m thinking anew the recitation of the biblical passages that say, “You shall not oppress a stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt” and “When strangers reside with you in your land, you shall not wrong them . . . You shall love them as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

My inclination is to understand this broadly—we are all responsible for all the strangers in our midst—rather than narrowly. My childhood Hebrew teachers said that this meant that Jews must look out for one another. This is consistent with how I think of Passover; but in the interests of full disclosure, I should add that a narrower interpretation would leave me doing all the dishes at the end of the ceremony.

My family’s Passover Seder is such a mixed lot of Jews, Christians, Buddhists, and agnostics that I’m sure we’re going to open the door for the prophet Elijah some day and get the Easter bunny instead. Of course Passover is an easy holiday to celebrate with people who have to be told what they’re celebrating. It fulfills a commandment that says, “You shall tell your child on this day” and is based on the instruction book called the Haggadah. The entire ceremony is designed to explain itself. Participants are meant to ask questions: What are we doing here? Why is there a bone and an exploded egg (I’m a bad egg-roaster) and parsley and mushy things on a plate? Where’s the normal bread?

The answers are nice and concrete—and usually edible: We were slaves in a foreign land until God freed us, and so there’s salt water for tears and horseradish for bitterness, and we taste them both. Literally. The gloppy brown stuff (ours is made of apples and pecans) represents the mortar that the slaves used to stick bricks together while building cities for Pharaoh. And it’s spring and this is a festival about hope, so we eat bright springy green sprigs of parsley.

Mostly it’s a festival of freedom. Whose? Well, the Jews who were enslaved in Egypt, but even as a child I found that too limited an interpretation. I grew up during the civil rights movement. When we sang “Go Down, Moses” in second grade, I knew it was about Moses from my Sunday school classes, but I also knew it was about slaves in the United States and what Dr. King was saying on television. At my childhood Seder, we skipped a lot. Dad read, “‘The great Rabbi Hillel had much to say about this,’” adding, “but we don’t. Next page.” Still, at the end, I always felt my heart lift, because we, or the American slaves, or someone were free.

So when I moved to New York City and acquired a mostly Italian, partly Irish, slightly Japanese family, I wanted to do a Seder with them. Even with the help of a lot of friends named Schwartz, this was awkward. People who have been taught by nuns in the 1950s (much of my new family) tend to think of ritual as serious stuff. They were thinking, “This is holy! Shut up and be respectful.” It took a few years to persuade them that you’re supposed to get slightly drunk and argue.

Having people who have never been at a Seder before makes it a better holiday. Someone needs to be truly asking questions. It shouldn’t become rote, as it might be if it’s always your family and everyone already knows what comes next: here’s where we get horseradish on the tablecloth; here’s where Uncle Irving renews his annual argument with Grandpa Abe about something that happened in 1952. And with newcomers, it’s possible to get genuinely unexpected answers to some of the traditional questions. One year a Venetian-American guest listened to us struggle with the traditional end-of-Seder wish, “Next year may we be in Jerusalem,” when most of us present would have preferred to say, “Next year may we be in Venice.” So what do we make of that—we muttered, as we often mutter—and the Venetian lady said, “Doesn’t it mean that people want to be in their true home—a real place or a spiritual home, their personal Jerusalem?” We thought it might.

It is, of course, possible to do Seder as the story of one people’s freedom and triumph, and the Egyptians get what they deserve, so there. But it’s useful to remember that the angels take this point of view in the Bible, and God yells at them. Even though the Egyptians are the complete bad guys of the story, God says, “You can’t rejoice when some of my people are suffering.” So as part of the Seder, we diminish our full glass of wine—a symbol of joy—a drop for each plague, to mourn the suffering of the very people we were fleeing.

It’s not a Seder that would satisfy everyone. Elijah’s cup is from an old Metropolitan Opera production of Parsifal. Occasionally an Italian brings a Neapolitan Easter cake, though some years the brisket has to be kosher. I’ve cobbled together a Haggadah that makes the coming from slavery to freedom, from oppression to joy, as universal as possible. So: You shall partake of suffering everywhere, because you suffered. You shall remember the poor. You shall remember to hope. Next year, may all be free. And, “You shall not oppress a stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt” and “When strangers reside with you in your land, you shall not wrong them. They shall be like the native-born. You shall love them as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

This year I was thinking of “strangers in our land.” I’ve given tenement tours to: Third graders, children of immigrants, who tell me our tenement apartments look big to them because they share a single room with their brothers and sisters and parents; the woman who asked her English teacher if the ponds in Central Park were for doing the laundry, like where she came from; visitors who say they were engineers or doctors in the old country, but here they drive taxis or work in construction - sometimes mocked for having “funny accents,” they plan to send their children to college; and the immigrant from Trinidad who was at our Seder—a Baptist minister—who wept, saying that he missed his family but realized that the ties of friendship and ritual can create a new family and a new home, even while the people with whom he shares ties of blood are far away.

- Posted by Judy Levin, Tenement Museum educator

My inclination is to understand this broadly—we are all responsible for all the strangers in our midst—rather than narrowly. My childhood Hebrew teachers said that this meant that Jews must look out for one another. This is consistent with how I think of Passover; but in the interests of full disclosure, I should add that a narrower interpretation would leave me doing all the dishes at the end of the ceremony.

My family’s Passover Seder is such a mixed lot of Jews, Christians, Buddhists, and agnostics that I’m sure we’re going to open the door for the prophet Elijah some day and get the Easter bunny instead. Of course Passover is an easy holiday to celebrate with people who have to be told what they’re celebrating. It fulfills a commandment that says, “You shall tell your child on this day” and is based on the instruction book called the Haggadah. The entire ceremony is designed to explain itself. Participants are meant to ask questions: What are we doing here? Why is there a bone and an exploded egg (I’m a bad egg-roaster) and parsley and mushy things on a plate? Where’s the normal bread?

The answers are nice and concrete—and usually edible: We were slaves in a foreign land until God freed us, and so there’s salt water for tears and horseradish for bitterness, and we taste them both. Literally. The gloppy brown stuff (ours is made of apples and pecans) represents the mortar that the slaves used to stick bricks together while building cities for Pharaoh. And it’s spring and this is a festival about hope, so we eat bright springy green sprigs of parsley.

Mostly it’s a festival of freedom. Whose? Well, the Jews who were enslaved in Egypt, but even as a child I found that too limited an interpretation. I grew up during the civil rights movement. When we sang “Go Down, Moses” in second grade, I knew it was about Moses from my Sunday school classes, but I also knew it was about slaves in the United States and what Dr. King was saying on television. At my childhood Seder, we skipped a lot. Dad read, “‘The great Rabbi Hillel had much to say about this,’” adding, “but we don’t. Next page.” Still, at the end, I always felt my heart lift, because we, or the American slaves, or someone were free.

So when I moved to New York City and acquired a mostly Italian, partly Irish, slightly Japanese family, I wanted to do a Seder with them. Even with the help of a lot of friends named Schwartz, this was awkward. People who have been taught by nuns in the 1950s (much of my new family) tend to think of ritual as serious stuff. They were thinking, “This is holy! Shut up and be respectful.” It took a few years to persuade them that you’re supposed to get slightly drunk and argue.

Having people who have never been at a Seder before makes it a better holiday. Someone needs to be truly asking questions. It shouldn’t become rote, as it might be if it’s always your family and everyone already knows what comes next: here’s where we get horseradish on the tablecloth; here’s where Uncle Irving renews his annual argument with Grandpa Abe about something that happened in 1952. And with newcomers, it’s possible to get genuinely unexpected answers to some of the traditional questions. One year a Venetian-American guest listened to us struggle with the traditional end-of-Seder wish, “Next year may we be in Jerusalem,” when most of us present would have preferred to say, “Next year may we be in Venice.” So what do we make of that—we muttered, as we often mutter—and the Venetian lady said, “Doesn’t it mean that people want to be in their true home—a real place or a spiritual home, their personal Jerusalem?” We thought it might.

It is, of course, possible to do Seder as the story of one people’s freedom and triumph, and the Egyptians get what they deserve, so there. But it’s useful to remember that the angels take this point of view in the Bible, and God yells at them. Even though the Egyptians are the complete bad guys of the story, God says, “You can’t rejoice when some of my people are suffering.” So as part of the Seder, we diminish our full glass of wine—a symbol of joy—a drop for each plague, to mourn the suffering of the very people we were fleeing.

It’s not a Seder that would satisfy everyone. Elijah’s cup is from an old Metropolitan Opera production of Parsifal. Occasionally an Italian brings a Neapolitan Easter cake, though some years the brisket has to be kosher. I’ve cobbled together a Haggadah that makes the coming from slavery to freedom, from oppression to joy, as universal as possible. So: You shall partake of suffering everywhere, because you suffered. You shall remember the poor. You shall remember to hope. Next year, may all be free. And, “You shall not oppress a stranger, for you know the feelings of the stranger, having yourselves been strangers in the land of Egypt” and “When strangers reside with you in your land, you shall not wrong them. They shall be like the native-born. You shall love them as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

This year I was thinking of “strangers in our land.” I’ve given tenement tours to: Third graders, children of immigrants, who tell me our tenement apartments look big to them because they share a single room with their brothers and sisters and parents; the woman who asked her English teacher if the ponds in Central Park were for doing the laundry, like where she came from; visitors who say they were engineers or doctors in the old country, but here they drive taxis or work in construction - sometimes mocked for having “funny accents,” they plan to send their children to college; and the immigrant from Trinidad who was at our Seder—a Baptist minister—who wept, saying that he missed his family but realized that the ties of friendship and ritual can create a new family and a new home, even while the people with whom he shares ties of blood are far away.

- Posted by Judy Levin, Tenement Museum educator

Thursday, April 1, 2010

Poems of New York

April is National Poetry Month, and to celebrate, tonight we host poet and teacher Stephen Wolf, who also happens to be editor of a wonderful volume of New York-centric poems, I Speak of the City. He, along with young poets from the New York Writers Coalition, will read some of our favorite works by poets whose names you might recognize (Whitman, Ginsberg) and those you may not at all (Lindsay, Koch).

To get the ball rolling, here's a portion of a poem by Charles Hanson Towne called "Manhattan" that probably speaks to many of us. Read it aloud!

Manhattan

When, sick of all the sorrow and distress

That flourished in the City like foul weeds,

I sought the blue rivers and green, opulent meads,

And leagues of unregarded loneliness

Whereon no foot of man had seemed to press,

I did not know how great had been my needs,

How wise the woodland's gospels and her creeds,

How good her faith to one long comfortless.

But in the silence came a voice to me;

In every wind it murmured, and I knew

It would not cease, though far my heart might roam.

It called me in the sunrise and the dew,

At noon and twilight, sadly, hungrily,

The jealous City, whispering always -- "Home!"

To get the ball rolling, here's a portion of a poem by Charles Hanson Towne called "Manhattan" that probably speaks to many of us. Read it aloud!

Manhattan

When, sick of all the sorrow and distress

That flourished in the City like foul weeds,

I sought the blue rivers and green, opulent meads,

And leagues of unregarded loneliness

Whereon no foot of man had seemed to press,

I did not know how great had been my needs,

How wise the woodland's gospels and her creeds,

How good her faith to one long comfortless.

But in the silence came a voice to me;

In every wind it murmured, and I knew

It would not cease, though far my heart might roam.

It called me in the sunrise and the dew,

At noon and twilight, sadly, hungrily,

The jealous City, whispering always -- "Home!"

Labels:

New York City history,

poetry,

Tenement Talks

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)