Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions.

Did the residents of 97 Orchard Street have leases for the apartments they rented? What were the terms of these leases?

For much of the 19th century, real estate transactions were sealed by a verbal agreement. From 1863 to 1934, when 97 Orchard Street was a residence, tenants most likely had oral leases. It wasn't until the 1920s that Lower East Side residents moved towards written leases that were more protective of tenants.

This change developed after the New York legislature instituted the Emergency Rent Laws in 1919-1920. Following a severe housing shortage, with escalating rents and widespread evictions, as well as over a decade worth of agitation on the part of tenants associations, these laws placed unprecedented emphasis on tenants obtaining written leases.

Although the Emergency Rent Laws protected tenants who made oral leases, State legislators such as Charles Lockwood and Samuel Untermeyer continually stated that written leases constituted tenants’ only real protection against illegal rent hikes and evictions.

The potential confusion and trouble caused by oral agreements was born out at 97 Orchard Street. On October 3, 1869, 97 Orchard Street resident and Hanover-born real estate broker Heinrich Dreyer met German-born baker Louis Rauch in a saloon on Avenue A. According to Dreyer, Rauch employed him to broker the sale of his bakery at the price of $3500. At that time, the two agreed that Dreyer would receive a 5% commission of $175 for arranging the sale.

According to an October 1870 court case involving Dreyer as the plaintiff and Rauch, Mr. Frederick Schmitt, and Mr. Christopher Weinz as defendants, Rauch never paid Dreyer the promised commission.

In fact, two other real estate agents claim to have brokered the sale of Mr. Rauch’s bakery at 115 Avenue A to Mr. John Rash on January 20, 1870 and were therefore each entitled to the commission.

The court determined that although Rauch made verbal agreements with all three real estate agents (Dreyer, Schmitt, and Rauch), only Schmitt had introduced buyer and seller in person. It was on this basis that the commission was awarded to Frederick Schmitt.

-- Posted by Kate

Monday, November 30, 2009

Wednesday, November 25, 2009

Happy Thanksgiving!

In the midst of the American Civil War, on October 3, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln decreed that the last Thursday of November would henceforth be "a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens."

The holiday had been celebrated unofficially since the 17th century and was made an official national holiday by President George Washington on October 3, 1789.

Interestingly, both men used this day of Thanksgiving to unite the nation.

In 1789, Washington decreed "Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being... That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks -- for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation... for the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted." (By October 1789, 11 states had ratified the Constitution, including New York.)

Seventy-four years later, Lincoln asked the nation to give thanks for its blessings even in the midst of crushing war: new freedom (Emancipation), peace and order (after bloody draft riots in New York and elsewhere), and the abundance of the frontier (work began on the Trans-Continental Railroad that year).

He wrote, "It has seemed to me fit and proper that [the gracious gifts of the Most High God] should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and voice by the whole American people. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens."

For newcomers to America, who came in large numbers from the German states and Ireland during the mid-19th century, Thanksgiving provided a chance to give thanks for a new home, a new job, safety, freedom. Perhaps the new residents of 97 Orchard Street, constructed that year, were thankful for new housing. The holiday also provided an opportunity for all Americans (native or foreign born, Northern or Southern) to come together around a singular national holiday.

This Thomas Nast illustration from the November 20, 1869 issue of Harper's Weekly shows a number of different people sharing a turkey at the table of "self-government" and "universal suffrage." Nast was never particularly sympathetic towards immigrants, so this cartoon is most likely poking fun.

Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The holiday had been celebrated unofficially since the 17th century and was made an official national holiday by President George Washington on October 3, 1789.

Interestingly, both men used this day of Thanksgiving to unite the nation.

In 1789, Washington decreed "Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being... That we may then all unite in rendering unto him our sincere and humble thanks -- for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation... for the peaceable and rational manner, in which we have been enabled to establish constitutions of government for our safety and happiness, and particularly the national One now lately instituted." (By October 1789, 11 states had ratified the Constitution, including New York.)

Seventy-four years later, Lincoln asked the nation to give thanks for its blessings even in the midst of crushing war: new freedom (Emancipation), peace and order (after bloody draft riots in New York and elsewhere), and the abundance of the frontier (work began on the Trans-Continental Railroad that year).

He wrote, "It has seemed to me fit and proper that [the gracious gifts of the Most High God] should be solemnly, reverently and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and voice by the whole American people. I do therefore invite my fellow citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next, as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the Heavens."

For newcomers to America, who came in large numbers from the German states and Ireland during the mid-19th century, Thanksgiving provided a chance to give thanks for a new home, a new job, safety, freedom. Perhaps the new residents of 97 Orchard Street, constructed that year, were thankful for new housing. The holiday also provided an opportunity for all Americans (native or foreign born, Northern or Southern) to come together around a singular national holiday.

This Thomas Nast illustration from the November 20, 1869 issue of Harper's Weekly shows a number of different people sharing a turkey at the table of "self-government" and "universal suffrage." Nast was never particularly sympathetic towards immigrants, so this cartoon is most likely poking fun.

Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Monday, November 23, 2009

A Lower East Side Anniversary

One hundred and forty-five years ago this month, Mr. John Schneider opened his lager-beer saloon at 97 Orchard Street.

On November 11, 1864 he placed an ad in the New-Yorker Staats-Zeitung, a leading German-language newspaper, which read:

The undersigned makes announcement to his fine friends and acquaintances as well as the honorable musicians, that he has taken over by purchase the saloon of Mr. Schurlein, 97 Orchard Street

John Schneider

Why might Mr. Schneider have mentioned "honorable musicians" in his announcement?

The family had a strong connection to music. John Schneider played in a regimental band with the 8th New York Infantry Volunteers during the Civil War. Most likely, the "honorable musicians" are those who played with him in 1860-62. His father, George, was also a respected musician on New York's German music scene. Because of his personal interest, John probably made an extra effort to provide music for his patrons on a regular basis.

Regarding German saloons on the Bowery in 1881, one observer commented, “Almost every beer saloon has a brass band, or at least a piano, violin, and coronet, and what the performers lack in finish they make up for in vigor. Through the open doors and from the cellars come outbursts of noise and merriment..."

According to historian Madelon Powers, German immigrants were fond of mixing drink and song, and were noted for their spontaneous saloon singing. Writing about the music of German saloons in turn-of-the-century Chicago, Royal Melendy observed that, “The streets are filled with music, and the German bands go from saloon to saloon reaping a generous harvest when times are good.”1

The most common form of German-American music during the mid-to-late 19th century was choral music performed by singing societies that often met in saloon backrooms. It is likely that John Schneider’s saloon included a small stage or area where music was performed by local singing societies or mannerchor and small German bands.

Many of the songs that became popular among German immigrants and the singing societies in which they took part expressed an ambivalence about the experience of leaving friends and family for an unknown land. Songs such as Muss I denn zum Stadtele N’Aus? (Must I Go Away from the Town?) and The Decision to Go to America; or, The Farewell Song of the Brothers expressed both an understanding of the need emigrate as well as the pain of leaving loved ones.

Informal and spontaneous singing was also common in 19th century German saloons. When in a singing mood, patrons of Schneider’s Saloon might break into a rendition of Auch du leiber Augustin, Hi-lee! Hilo! or Die Wacht am Rhein.

Groups of saloon regulars not only broke into song for the purpose of entertainment but also as a means of strengthening group identity. Sung widely in informal settings such as the local saloon, heimathlied or “homesickness” songs not only helped German immigrants reinforce ties to the Fatherland but -- many Germans having emigrated before the creation of the German nation in 1871 -- helped contribute to a new consciousness among German immigrants, unifying these fragmented elements into an American ethnic community. 2

___________________________

1 Madelon Powers, Faces Along the Bar: Lore and Order in the Workingman’s Saloon, 1870-1920 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998)

2 Victor Greene, A Singing Ambivalence: Immigrants Between Old World and New (Kent State University Press, 2004).

- Research & Writing by Dave Favaloro

Friday, November 20, 2009

Friday Immigration News (plus Housing & Health)

Puerto Ricans in New York Face Persistent Struggles

(WNYC, November 20, 2009) Puerto Rican leaders have made lots of news this year – from Sonia Sotomayor’s rise to the Supreme Court, to the so-called ‘three amigos’ who took power in the New York legislature. While New York’s most visible Latino leaders are Puerto Rican…some researchers are trying to call attention to a less visible reality: that almost a third of Puerto Ricans are living below the poverty line, compared to less than a fifth of all New Yorkers. And in educational and professional achievement, New York’s Puerto Ricans are doing worse than Latinos as a whole. WNYC’s Marianne McCune reports.

U.S. DHS Head Insists Immigration Reform Is Key

(Carib World News, Nov. 20, 2009)

"The need for immigration reform is so clear," insists the US Homeland Security Chief, Janet Napolitano. In remarks this week to the Center for American Progress, Napolitano insisted that President Obama is committed to this issue and "the administration does not shy away from taking on the big challenges of the 21st century, challenges that have been ignored too long and hurt our families and businesses."

Exhibit documents immigrants’ stories

(The Galviston County Daily News, Nov. 20, 2009)

The traveling exhibit Forgotten Gateway chronicles the Port of Galveston, Texas’s largely forgotten history as a major gateway to American immigration from 1845 to 1924. Forgotten Gateway builds on a growing scholarly and public interest in the history of migration patterns to America and Galveston’s place as one of the nation’s top immigrant ports in that history.

Immigration Reform: The Phone Call Heard Around the Country

(New American Media, Nov. 19, 2009) Organizers described them as immigration reform "house parties." Across the country last night, in churches, schools, immigrant support centers and private homes, backers of immigration reform gathered around telephones (the speaker phone turning the device into a de-facto radio) as Hispanic U.S. legislators laid out the strategy for pushing a reform of the immigration system in 2010.

Fire Reveals Illegal Homes Hide in Plain Sight

(New York Times, Nov. 19, 2009)

For at least two years before a fire killed three men in an illegally divided house next door, Diane Ross and her family lived in an illegal apartment at 42-38 65th Street in Woodside, Queens. Their life there — in a basement divided into one apartment and four single-room units, with six others upstairs, all crammed into a two-family house — seemed to them to be business as usual, and attracted no special notice. Neither the tenants nor their landlord, who said he charged $107 a month for each room, tried to hide it.

Sir John Crofton, Pioneer in TB Cure, Dies at 97

(New York Times, Nov. 19, 2009)

Sir John Crofton, a pioneering clinician who demonstrated that antibiotics could be safely combined to cure tuberculosis, a dread disease that once killed half the people who contracted it, died on Nov. 3 at his home in Edinburgh. He was 97.

(WNYC, November 20, 2009) Puerto Rican leaders have made lots of news this year – from Sonia Sotomayor’s rise to the Supreme Court, to the so-called ‘three amigos’ who took power in the New York legislature. While New York’s most visible Latino leaders are Puerto Rican…some researchers are trying to call attention to a less visible reality: that almost a third of Puerto Ricans are living below the poverty line, compared to less than a fifth of all New Yorkers. And in educational and professional achievement, New York’s Puerto Ricans are doing worse than Latinos as a whole. WNYC’s Marianne McCune reports.

U.S. DHS Head Insists Immigration Reform Is Key

(Carib World News, Nov. 20, 2009)

"The need for immigration reform is so clear," insists the US Homeland Security Chief, Janet Napolitano. In remarks this week to the Center for American Progress, Napolitano insisted that President Obama is committed to this issue and "the administration does not shy away from taking on the big challenges of the 21st century, challenges that have been ignored too long and hurt our families and businesses."

Exhibit documents immigrants’ stories

(The Galviston County Daily News, Nov. 20, 2009)

The traveling exhibit Forgotten Gateway chronicles the Port of Galveston, Texas’s largely forgotten history as a major gateway to American immigration from 1845 to 1924. Forgotten Gateway builds on a growing scholarly and public interest in the history of migration patterns to America and Galveston’s place as one of the nation’s top immigrant ports in that history.

Immigration Reform: The Phone Call Heard Around the Country

(New American Media, Nov. 19, 2009) Organizers described them as immigration reform "house parties." Across the country last night, in churches, schools, immigrant support centers and private homes, backers of immigration reform gathered around telephones (the speaker phone turning the device into a de-facto radio) as Hispanic U.S. legislators laid out the strategy for pushing a reform of the immigration system in 2010.

Fire Reveals Illegal Homes Hide in Plain Sight

(New York Times, Nov. 19, 2009)

For at least two years before a fire killed three men in an illegally divided house next door, Diane Ross and her family lived in an illegal apartment at 42-38 65th Street in Woodside, Queens. Their life there — in a basement divided into one apartment and four single-room units, with six others upstairs, all crammed into a two-family house — seemed to them to be business as usual, and attracted no special notice. Neither the tenants nor their landlord, who said he charged $107 a month for each room, tried to hide it.

Sir John Crofton, Pioneer in TB Cure, Dies at 97

(New York Times, Nov. 19, 2009)

Sir John Crofton, a pioneering clinician who demonstrated that antibiotics could be safely combined to cure tuberculosis, a dread disease that once killed half the people who contracted it, died on Nov. 3 at his home in Edinburgh. He was 97.

Labels:

current immigration,

health,

housing,

immigration news

Thursday, November 19, 2009

New finds in 97 Orchard Street basement

We uncovered more spaces in the rear of the basement. This is an area we believe was once a residential apartment. The brick was covered with sheetrock. We removed it to have a look at what was underneath.

Here's one of the fireplaces. You can see that it's been boarded up.

This fireplace was not boarded up quite so professionally. Bob, Chris and Derya could easily get into an open space at the top and begin to sift through some of the debris that fills the fireplace cavity.

Here's the back of a piece of sheetrock. It should give us a clue as to when the sheetrock was installed.

We found a table knife, all rusted over.

We found this letter. It says, "Scher's Jobbing House, 97 Orchard Street, NYC." The return address is pre-printed on the upper left-hand corner: PO Box 743, City Hall Station, New York, NY. It was posted on July 19, 1933 at 6 PM, passing through "City Hall Annex New York."

A man named Scher was a mentor to Max Marcus, who ran an auction house in 97 Orchard Street in the 1930s. We won't be able to open the letter until it's been "re-humidified." Right now it's brittle and we don't want to damage the envelope or the contents. Derya will put it in a humidity chamber to soften it out a bit.

What could be inside? And how did a letter end up in a boarded-up basement fireplace? We shall report back to you on the former very soon, and feel free to speculate about the latter...

- posted by kate

Labels:

97 Orchard Street,

artifacts,

schneider's saloon

Wednesday, November 18, 2009

The Begecher Family History, Part 3

The story of the Begecher Family, who lived at 103 Orchard Street in the early 20th century, continues below. Read parts one and two. Research and writing by Alan Kurtz. Special thanks to Bowery Boogie.

On December 14th of 1904, five years after his arrival (the minimum time required by law), Marcus became an American citizen, taking the oath at the United States Eastern District Court. His Petition for Naturalization described him as a peddler living at 103 Orchard Street and noted that he could not read or write English but could “read and write the Hebrew language intelligently.” It wasn’t until 1906 that prospective citizens were required to know English.

Though much of the 1905 New York State Census has been lost, a hand-copied facsimile dating to the 1940s records the family as Max, Sarah, Ida, Lena, Rosa, Mendel, Sam, and Jackel Bulchecher. Max listed his occupation as peddler, Ida and Lena worked in “ladies wear,” while Sam and Jackel attended elementary school. Rosa and Mandel’s given occupations are not legible.

Five years later, at the time of the 1910 Federal Census, the family still resided on Orchard Street and were enumerated on April 16th under the names Marcus, Sabra, Ida, Max, Rose, Samuel, and Jacob Buchacher. Lilly was living elsewhere. Marcus was recorded as a salesman in a dry goods store, Ida and Rose as operators in a tailor shop, Max as a truck driver, and Sam an office boy. Unfortunately, their apartment number was not recorded. Whether Marcus, Ida, and Rose were still working for their more well-off Bralower relations is not known.

Two months later, on June 8, 1910 Ida Buchesser, age 23, married Max Katz, a 30 year old widower with a young son, and moved to the far reaches of the Bronx.

At some juncture during the early to mid 1910s, possibly when the building underwent extensive renovation in 1913, the family moved from 103 Orchard Street around the corner to 247 Broome Street. The family surname continued to evolve: Sam would retain the name Begecher, Max and Lilly would adopt the name Schesser, while Jack would somehow morph into Jack Schwartz.

Marcus and Sarah died within one year of each other: Marcus on May 22, 1923 and Sarah on May 12, 1924. They are buried in Acacia Cemetery in Ozone Park, Queens. Though their Death Certificates carry the surname of "Schesser," their headstones are inscribed "Betchesser."

Ida Begecher Katz died on January 24, 1961, having outlived her husband Max by almost 28 years.

Eventually all surviving family members would leave the Lower East Side.

My wife is the granddaughter of Ida Begecher Katz and great-granddaughter of Marcus and Sarah Begecher.

Do you have any information about 103 or 97 Orchard Street? Any memories of the people who lived there? Share them with us! Email press-inquiry (at) tenement . org.

- Posted by Kate

On December 14th of 1904, five years after his arrival (the minimum time required by law), Marcus became an American citizen, taking the oath at the United States Eastern District Court. His Petition for Naturalization described him as a peddler living at 103 Orchard Street and noted that he could not read or write English but could “read and write the Hebrew language intelligently.” It wasn’t until 1906 that prospective citizens were required to know English.

Marcus Begecher’s Petition for Naturalization: his address is 103 Orchard Street

Though much of the 1905 New York State Census has been lost, a hand-copied facsimile dating to the 1940s records the family as Max, Sarah, Ida, Lena, Rosa, Mendel, Sam, and Jackel Bulchecher. Max listed his occupation as peddler, Ida and Lena worked in “ladies wear,” while Sam and Jackel attended elementary school. Rosa and Mandel’s given occupations are not legible.

Five years later, at the time of the 1910 Federal Census, the family still resided on Orchard Street and were enumerated on April 16th under the names Marcus, Sabra, Ida, Max, Rose, Samuel, and Jacob Buchacher. Lilly was living elsewhere. Marcus was recorded as a salesman in a dry goods store, Ida and Rose as operators in a tailor shop, Max as a truck driver, and Sam an office boy. Unfortunately, their apartment number was not recorded. Whether Marcus, Ida, and Rose were still working for their more well-off Bralower relations is not known.

1910 Federal Census record for 103 Orchard Street; the family is listed in the middle.

Two months later, on June 8, 1910 Ida Buchesser, age 23, married Max Katz, a 30 year old widower with a young son, and moved to the far reaches of the Bronx.

At some juncture during the early to mid 1910s, possibly when the building underwent extensive renovation in 1913, the family moved from 103 Orchard Street around the corner to 247 Broome Street. The family surname continued to evolve: Sam would retain the name Begecher, Max and Lilly would adopt the name Schesser, while Jack would somehow morph into Jack Schwartz.

Jack and Lilly

Marcus and Sarah died within one year of each other: Marcus on May 22, 1923 and Sarah on May 12, 1924. They are buried in Acacia Cemetery in Ozone Park, Queens. Though their Death Certificates carry the surname of "Schesser," their headstones are inscribed "Betchesser."

Ida Begecher Katz died on January 24, 1961, having outlived her husband Max by almost 28 years.

Eventually all surviving family members would leave the Lower East Side.

My wife is the granddaughter of Ida Begecher Katz and great-granddaughter of Marcus and Sarah Begecher.

Do you have any information about 103 or 97 Orchard Street? Any memories of the people who lived there? Share them with us! Email press-inquiry (at) tenement . org.

- Posted by Kate

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

The Begecher Family History, Continued

The story of the Begecher Family, who lived at 103 Orchard Street in the early 20th century, continues below. Read part one here. Research and writing by Alan Kurtz. Special thanks to Bowery Boogie.

On July 9, 1899 Ida and Lilly’s father, listed on the steamship Friesland’s manifest as "Markus Boczezcer," a 54-year-old laborer, arrived from Antwerp, Belgium with one dollar to his name. Though quite young, Ida (and perhaps Lilly) had apparently saved enough money to at least contribute to the cost of his ticket.

He was briefly detained at the Barge Office at the Battery, most likely because immigration officials feared that he wouldn't be able to earn a living and thus become a “Public Charge.” (He came through the Battery because the original buildings at Ellis Island burned down in 1897, and the new brick buildings were still under construction at this time.)

Markus was probably released under the aegis of his brother-in-law Louis. Just nine days after his arrival, Marcus Begecher filed his Declaration of Intention (commonly called “First Papers” as they constituted the first step in the naturalization process) with the Southern District Circuit Court of the United States to become an American citizen: certainly a statement of commitment to his new and adopted country.

It would be three long years before the family was entirely reunited. Sarah, Mendel, Ruchel, Schema, and Snerza (Mendel would eventually become Max, Ruchel Rose, Schema Sam, and Schnerza Jack) arrived on the steamship La Bretagne sailing from Le Havre, France on September 7, 1902. The New York Times reported the weather as "cloudy; warmer; showers; southeast winds.”

The manifest records them as the "Bucecer" family. They were briefly detained at Ellis Island before Marcus arrived and obtained their release; La Bretagne had docked shortly after daybreak and the family was released at 2:35 in the afternoon. During their time in “detention” the family consumed five meals; one for each family member.

Sarah was not only reunited with her brother, Louis; her husband; and her two eldest daughters but also with additional siblings and her aged mother, Anyavita Bralower, who had come to America sometime during the 1890s.

Though it seems as if the family initially shared crowded living space with the Bralower family (Sarah's relations) on Hester Street, they soon moved to Eldridge Street (near Delancey Street) before relocating to 103 Orchard Street sometime before December of 1904.

...To be continued tomorrow, as the family makes a home on the Lower East Side.

- Posted by Kate

On July 9, 1899 Ida and Lilly’s father, listed on the steamship Friesland’s manifest as "Markus Boczezcer," a 54-year-old laborer, arrived from Antwerp, Belgium with one dollar to his name. Though quite young, Ida (and perhaps Lilly) had apparently saved enough money to at least contribute to the cost of his ticket.

He was briefly detained at the Barge Office at the Battery, most likely because immigration officials feared that he wouldn't be able to earn a living and thus become a “Public Charge.” (He came through the Battery because the original buildings at Ellis Island burned down in 1897, and the new brick buildings were still under construction at this time.)

Markus was probably released under the aegis of his brother-in-law Louis. Just nine days after his arrival, Marcus Begecher filed his Declaration of Intention (commonly called “First Papers” as they constituted the first step in the naturalization process) with the Southern District Circuit Court of the United States to become an American citizen: certainly a statement of commitment to his new and adopted country.

It would be three long years before the family was entirely reunited. Sarah, Mendel, Ruchel, Schema, and Snerza (Mendel would eventually become Max, Ruchel Rose, Schema Sam, and Schnerza Jack) arrived on the steamship La Bretagne sailing from Le Havre, France on September 7, 1902. The New York Times reported the weather as "cloudy; warmer; showers; southeast winds.”

The manifest records them as the "Bucecer" family. They were briefly detained at Ellis Island before Marcus arrived and obtained their release; La Bretagne had docked shortly after daybreak and the family was released at 2:35 in the afternoon. During their time in “detention” the family consumed five meals; one for each family member.

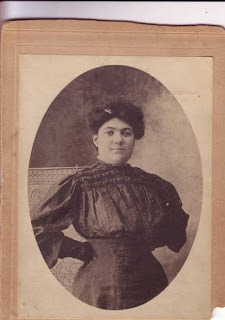

Sarah Bralower Begecher

Sarah was not only reunited with her brother, Louis; her husband; and her two eldest daughters but also with additional siblings and her aged mother, Anyavita Bralower, who had come to America sometime during the 1890s.

Though it seems as if the family initially shared crowded living space with the Bralower family (Sarah's relations) on Hester Street, they soon moved to Eldridge Street (near Delancey Street) before relocating to 103 Orchard Street sometime before December of 1904.

...To be continued tomorrow, as the family makes a home on the Lower East Side.

- Posted by Kate

Monday, November 16, 2009

The Begechers of 103 Orchard Street

When you are in the research business, sometimes you get lucky and things just come to you. A genealogist working for the Museum back in the early 1990s was handed the wrong file at an archive, and inside - quite by accident - was a letter of support for 97 Orchard Street resident Nathalie Gumpertz's petition to declare her husband legally dead. This story now forms the basis of the Getting By tour.

Last week, out of the blue, Bowery Boogie sent me an email - a Mr. Allen Kurtz had read on that blog about the Tenement Museum's research into 103 Orchard Street and wrote in to say, "My wife's family lived in that building from 1904 to 1910." As if that weren't cool enough on its own, Mr. Kurtz then sent along an extensive family history, charting the Begechers' arrival in the United States and their path through 103 Orchard Street and beyond.

I'm very happy to share that history with you this week. What's wonderful is how typical this immigrant experience is... and yet so personal to this distinct family.

Special thanks to Bowery Boogie.

The Begechers of 103 Orchard Street

By Alan Kurtz

In many ways, the Begechers (Marcus, Sarah, and their six children, Chaya, Liebe, and Ruchel, Mendel, Schema, and Schnerza) were typical Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Originally from Botosani, a small city in what is today northeast Romania, they more likely than not came to the United States to escape a life severely limited by persecution, oppression, and grinding poverty.

Not able to afford passage for the family to depart for America as an intact unit, the Begechers arrived in dribs and drabs as if a human chain; one saving up hard earned dollars to purchase passage for the next. Consequently, family members were often separated for months if not years.

Though it cannot be proven with complete accuracy, Chaya (who would subsequently Americanize her name to Ida) was likely the first to arrive, possibly sometime in 1898. Because she was still a child, perhaps as young as eight years of age, she came to America not in steerage, but as a Second Class passenger.

As steamship lines were not required to record their “better heeled” First and Second Class passengers on official manifests until 1903, her exact arrival date is not known, and it may be that she didn’t arrive until 1901.

Similarly, the name of the person who accompanied her to America is a perplexing mystery. What is known is that the man, who Ida would describe later in life as either an agent or an “uncle,” was quite protective of her and would not let her go down to steerage to meet other young passengers. As a result, she had no one to play with. All the while, she suffered from seasickness.

Her passage was paid for by her aunt and uncle, Celia and Louis Bralower of 50-52 Hester Street, who owned a thriving dry goods business. Their company, established in the 1880s, would survive for nearly 100 years.

Immediately after arrival, Ida was put to work in their shop to pay off her passage. Ida’s sister Liebe, who would later change her name to Lilly, may have arrived shortly thereafter. Her arrival manifest has also not been located.

To be continued tomorrow... as the rest of the family arrives in America.

- posted by Kate

Last week, out of the blue, Bowery Boogie sent me an email - a Mr. Allen Kurtz had read on that blog about the Tenement Museum's research into 103 Orchard Street and wrote in to say, "My wife's family lived in that building from 1904 to 1910." As if that weren't cool enough on its own, Mr. Kurtz then sent along an extensive family history, charting the Begechers' arrival in the United States and their path through 103 Orchard Street and beyond.

I'm very happy to share that history with you this week. What's wonderful is how typical this immigrant experience is... and yet so personal to this distinct family.

Special thanks to Bowery Boogie.

The Begechers of 103 Orchard Street

By Alan Kurtz

In many ways, the Begechers (Marcus, Sarah, and their six children, Chaya, Liebe, and Ruchel, Mendel, Schema, and Schnerza) were typical Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Originally from Botosani, a small city in what is today northeast Romania, they more likely than not came to the United States to escape a life severely limited by persecution, oppression, and grinding poverty.

Not able to afford passage for the family to depart for America as an intact unit, the Begechers arrived in dribs and drabs as if a human chain; one saving up hard earned dollars to purchase passage for the next. Consequently, family members were often separated for months if not years.

Though it cannot be proven with complete accuracy, Chaya (who would subsequently Americanize her name to Ida) was likely the first to arrive, possibly sometime in 1898. Because she was still a child, perhaps as young as eight years of age, she came to America not in steerage, but as a Second Class passenger.

As steamship lines were not required to record their “better heeled” First and Second Class passengers on official manifests until 1903, her exact arrival date is not known, and it may be that she didn’t arrive until 1901.

Similarly, the name of the person who accompanied her to America is a perplexing mystery. What is known is that the man, who Ida would describe later in life as either an agent or an “uncle,” was quite protective of her and would not let her go down to steerage to meet other young passengers. As a result, she had no one to play with. All the while, she suffered from seasickness.

Ida Begecher Katz, later in life. Courtesy Alan Kurtz.

Her passage was paid for by her aunt and uncle, Celia and Louis Bralower of 50-52 Hester Street, who owned a thriving dry goods business. Their company, established in the 1880s, would survive for nearly 100 years.

Immediately after arrival, Ida was put to work in their shop to pay off her passage. Ida’s sister Liebe, who would later change her name to Lilly, may have arrived shortly thereafter. Her arrival manifest has also not been located.

To be continued tomorrow... as the rest of the family arrives in America.

- posted by Kate

Friday, November 13, 2009

Questions for Curatorial - Restriction, Exclusion, and Quotas

Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions.

Was there a ban on certain immigrant groups moving into 97 Orchard Street at any time in the building’s history?

Legislative acts banning certain immigrant groups from the United States were first instituted during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, though nativism and anti-immigrant sentiment are as old as immigration itself.

Passed in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act represented the first federal law banning a group of immigrants solely on the basis of race or nationality. In 1917, Congressional legislation further restricted immigration by barring the entry of Asian Indians. A prohibition on Japanese and Korean immigration followed in 1922 so that, after 1924, among East Asians only Filipinos were untouched by immigration restriction laws.

Beginning in the 1920s, Congress passed a series of quota laws aimed at stemming the mass immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans that had occurred over the course of the past two decades.

Each European nation received a quota based on its proportion to the foreign-born population in the 1910 census, resulting in a drastic reduction in the number of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. In 1929, another system, the national origins quotas, was put into effect, giving each European country a proportion equal to its share of the white population according to the 1920 census.

Was there a ban on certain immigrant groups moving into 97 Orchard Street at any time in the building’s history?

Legislative acts banning certain immigrant groups from the United States were first instituted during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, though nativism and anti-immigrant sentiment are as old as immigration itself.

Passed in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act represented the first federal law banning a group of immigrants solely on the basis of race or nationality. In 1917, Congressional legislation further restricted immigration by barring the entry of Asian Indians. A prohibition on Japanese and Korean immigration followed in 1922 so that, after 1924, among East Asians only Filipinos were untouched by immigration restriction laws.

Beginning in the 1920s, Congress passed a series of quota laws aimed at stemming the mass immigration of Southern and Eastern Europeans that had occurred over the course of the past two decades.

Each European nation received a quota based on its proportion to the foreign-born population in the 1910 census, resulting in a drastic reduction in the number of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. In 1929, another system, the national origins quotas, was put into effect, giving each European country a proportion equal to its share of the white population according to the 1920 census.

Thursday, November 12, 2009

Antique Footwear!

If you haven't seen it already, check out this trove of old rubber boots found in the Mark Miller gallery space across the street from the Museum.

The video and photos we took are posted on the Bowery Boogie blog.

Here's a little video of the guy who was doing excavation work in the basement taking a giant lump of fused rubber boots to the dumpster.

Here are some of the photos along with some info about the shoes from Derya, our collections manager.

Boy, do we wish these shoes were from 97 Orchard Street! They would be a great find for our new storefronts exhibit.

The video and photos we took are posted on the Bowery Boogie blog.

Here's a little video of the guy who was doing excavation work in the basement taking a giant lump of fused rubber boots to the dumpster.

Here are some of the photos along with some info about the shoes from Derya, our collections manager.

Boy, do we wish these shoes were from 97 Orchard Street! They would be a great find for our new storefronts exhibit.

Questions for Curatorial - Castle Garden

Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions.

Before Castle Garden was opened in 1855, where were immigrants entering through the port of New York processed?

Before Castle Garden was designated as the central landing place for all immigrants disembarking at the port of New York in 1855, new arrivals came ashore at several different piers along the East River. While immigrants reported to be carrying communicable diseases were quarantined at the Marine Hospital on Staten Island, there was little formal processing that occurred.

Once newcomers disembarked, they were met by often unscrupulous runners—agents of boarding houses and companies that transported immigrants to the interior of the country. Frequently of the same ethnicity and speaking the same language, these runners repeatedly took advantage of new immigrants, overcharging them for rents at boarding houses and rail and steam ship tickets.

Interior of Castle Garden. Harper's Weekly, 1871. Courtesy the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library.

Immigrants landing at Castle Garden. Harper's Weekly, 1880. Courtesy the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library.

In 1847, the New York State legislature established the Board of Commissioners of Emigration. According to historians Frederick Binder and David Reimers, “They were given both the power and the funds to inspect incoming ships and provide aid, information, and employment assistance to the immigrants.”

Opened in 1855, Castle Garden at the southern tip of Manhattan was created by the State of New York to process new immigrants and help them make the transition to the United States. There, immigrants could avoid runners by purchasing railroad and riverboat tickets from reputable vendors, obtain advice from representatives of religious and benevolent societies, and consult employment agencies staffed with translators. After 1892, responsibility for processing arriving immigrants fell to the Federal Government and Ellis Island in Upper New York Bay became the main point of entry for new immigrants.

Immigrants in Castle Garden. Harper's Weekly, 1880. Courtesy the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library.

Source: Frederick Binder and David Reimers, All the Nations Under Heaven: An Ethnic and Racial History of New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

Before Castle Garden was opened in 1855, where were immigrants entering through the port of New York processed?

Before Castle Garden was designated as the central landing place for all immigrants disembarking at the port of New York in 1855, new arrivals came ashore at several different piers along the East River. While immigrants reported to be carrying communicable diseases were quarantined at the Marine Hospital on Staten Island, there was little formal processing that occurred.

Once newcomers disembarked, they were met by often unscrupulous runners—agents of boarding houses and companies that transported immigrants to the interior of the country. Frequently of the same ethnicity and speaking the same language, these runners repeatedly took advantage of new immigrants, overcharging them for rents at boarding houses and rail and steam ship tickets.

Interior of Castle Garden. Harper's Weekly, 1871. Courtesy the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library.

Immigrants landing at Castle Garden. Harper's Weekly, 1880. Courtesy the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library.

In 1847, the New York State legislature established the Board of Commissioners of Emigration. According to historians Frederick Binder and David Reimers, “They were given both the power and the funds to inspect incoming ships and provide aid, information, and employment assistance to the immigrants.”

Opened in 1855, Castle Garden at the southern tip of Manhattan was created by the State of New York to process new immigrants and help them make the transition to the United States. There, immigrants could avoid runners by purchasing railroad and riverboat tickets from reputable vendors, obtain advice from representatives of religious and benevolent societies, and consult employment agencies staffed with translators. After 1892, responsibility for processing arriving immigrants fell to the Federal Government and Ellis Island in Upper New York Bay became the main point of entry for new immigrants.

Immigrants in Castle Garden. Harper's Weekly, 1880. Courtesy the Picture Collection of the New York Public Library.

Source: Frederick Binder and David Reimers, All the Nations Under Heaven: An Ethnic and Racial History of New York City (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995).

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Questions for Curatorial - the Influenza Outbreak of 1918

Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions.

Did any former residents of 97 Orchard Street die during the 1918 influenza epidemic?

Among the most deadly epidemics in human history, the 1918 Great Influenza pandemic killed approximately fifteen to twenty-one million people world wide. When it reached New York City during the fall of 1918, 130,000 people contracted the virus, and approximately 33,000 died by the time it had run its course in November 1918. Unfortunately, no statistical analysis of influenza deaths in 1918 by neighborhood has been conducted to date.

Nevertheless, the virus spread rapidly once it arrived in the crowded tenements of the Lower East Side—then considered the most densely populated place on earth with an average of approximately one thousand people per square acre—where it felled hundreds.

According to his daughters, Rumanian immigrant Jacob Burinescu died during the 1918 Influenza pandemic at 97 Orchard Street. Witness to the human toll wrought by the pandemic, one young Lower East Sider remembered that, “children died at an alarming rate and wagons came by on a regular basis to pick up the dead.”

Did any former residents of 97 Orchard Street die during the 1918 influenza epidemic?

Among the most deadly epidemics in human history, the 1918 Great Influenza pandemic killed approximately fifteen to twenty-one million people world wide. When it reached New York City during the fall of 1918, 130,000 people contracted the virus, and approximately 33,000 died by the time it had run its course in November 1918. Unfortunately, no statistical analysis of influenza deaths in 1918 by neighborhood has been conducted to date.

Nevertheless, the virus spread rapidly once it arrived in the crowded tenements of the Lower East Side—then considered the most densely populated place on earth with an average of approximately one thousand people per square acre—where it felled hundreds.

According to his daughters, Rumanian immigrant Jacob Burinescu died during the 1918 Influenza pandemic at 97 Orchard Street. Witness to the human toll wrought by the pandemic, one young Lower East Sider remembered that, “children died at an alarming rate and wagons came by on a regular basis to pick up the dead.”

Tuesday, November 10, 2009

Questions for Curatorial: The Significance of Bridges

Curatorial Director Dave answers your questions.

How did the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge affect people living on the Lower East Side?

The Brooklyn Bridge opened on May 24, 1883, instantly becoming the longest bridge in the world. As the first bridge connecting the cities of Brooklyn and New York (Manhattan), it offered a cheap alternative to the ferries that daily carried men back and forth between their homes and workplaces. It was also built largely by immigrant workers, many of whom lived on the Lower East Side.

When the Brooklyn Elevated to Fulton Ferry was completed in 1885, providing easy access to the interior of Brooklyn, traffic on the Bridge more than doubled, so that by 1885 it was handling some 20 million passengers a year.

For this reason, it undoubtedly aided the exodus of those immigrants and children of immigrants able to afford homes in Brooklyn and the daily commute by street car into the city. While the dispersal of the Lower East Side’s German and Irish immigrant communities was already well underway, the opening the Brooklyn bridge likely hastened their exodus.

But 25 years after it opened, the Lower East Side reached its peak population density.

Built in 1903, the Williamsburg Bridge had a greater effect on the ability of immigrants to leave the Lower East Side. In the early 20th century, the bridge was seen as a passageway to a new life in Williamsburg, Brooklyn by thousands of Jewish immigrants fleeing the overcrowded neighborhood.

Even more important was the inauguration of the subway in 1904, whose extension over the next several decades allowed for the further decentralization of the city by making rapid transportation accessible to the working-class New Yorker. Once subway lines had been extended to places like Brownsville and East New York in Brooklyn, these areas became second Lower East Sides — immigrant neighborhoods that provided homes, workplaces, and communities to thousands of new Americans.

(Images courtesy New York Public Library - United States in Stereo: In the Robert N. Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views; and United States History, Local History and Genealogy Division.)

How did the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge affect people living on the Lower East Side?

The Brooklyn Bridge opened on May 24, 1883, instantly becoming the longest bridge in the world. As the first bridge connecting the cities of Brooklyn and New York (Manhattan), it offered a cheap alternative to the ferries that daily carried men back and forth between their homes and workplaces. It was also built largely by immigrant workers, many of whom lived on the Lower East Side.

When the Brooklyn Elevated to Fulton Ferry was completed in 1885, providing easy access to the interior of Brooklyn, traffic on the Bridge more than doubled, so that by 1885 it was handling some 20 million passengers a year.

For this reason, it undoubtedly aided the exodus of those immigrants and children of immigrants able to afford homes in Brooklyn and the daily commute by street car into the city. While the dispersal of the Lower East Side’s German and Irish immigrant communities was already well underway, the opening the Brooklyn bridge likely hastened their exodus.

But 25 years after it opened, the Lower East Side reached its peak population density.

Built in 1903, the Williamsburg Bridge had a greater effect on the ability of immigrants to leave the Lower East Side. In the early 20th century, the bridge was seen as a passageway to a new life in Williamsburg, Brooklyn by thousands of Jewish immigrants fleeing the overcrowded neighborhood.

Even more important was the inauguration of the subway in 1904, whose extension over the next several decades allowed for the further decentralization of the city by making rapid transportation accessible to the working-class New Yorker. Once subway lines had been extended to places like Brownsville and East New York in Brooklyn, these areas became second Lower East Sides — immigrant neighborhoods that provided homes, workplaces, and communities to thousands of new Americans.

(Images courtesy New York Public Library - United States in Stereo: In the Robert N. Dennis Collection of Stereoscopic Views; and United States History, Local History and Genealogy Division.)

Monday, November 9, 2009

Tricks, Treats and Ghosts

Children often come into the museum’s slightly spooky, dark hallway and ask in fear, “Are there ghosts at 97 Orchard Street?” We say, “No.”

But this October 31, the Museum opened its doors for a special Family Halloween Celebration, and some unexpected specters were spotted in the halls.

The day began with cider and donuts, arts-and-crafts projects and a photo booth for vintage family photos. Large spotted spiders, cobwebs, and black crepe paper streamers turned the basement into a spooky party space.

Once guests were invited upstairs, they saw faces both old and new - Victoria Confino, part of the Confino Family Living History Tour, was busying about her kitchen as usual, but Harris Levine, Bridget Moore, and Rosaria and Adolfo Baldizzi were also at home this special morning.

All of our ghosts (In reality, costumed interpreters, of course) made charming hosts.

Victoria pointed out that our clothes looked pretty strange to her 1916 eyes: T-shirts and trousers on women seemed as peculiar as a young trick-or-treater dressed as a ballerina –

“You’re wearing your underwear on the outside?” Victoria asked about the tutu and tights. “Is that the custom where you come from?”

Bridget Moore, a tenant in 1869, was concerned that she couldn’t offer us tea. Harris Levine (who believed it was 1897) invited the 11-year-olds visiting his apartment to work full-time in his garment factory.

"Only ten hours a day - you can have the Sabbath off!"

Rosaria Baldizzi insisted that we call her Sadie.

“I have an American name now,” she explained.

She was packing and lamented the tenants’ recent eviction from the building after the new (1934) law requiring landlords to fireproof staircases in all tenements. The building, she reminded us, had been her home for many years. Her husband, Adolfo, mentioned their move too but was looking forward to the change.

For those of us who gives tours of the building, meeting this cast of characters in the flesh was unexpectedly moving. Even though those apparitions were just our coworkers in period costumes, they were a reminder that the stories we tell are true ones, that people really did live at 97 Orchard, and that their lives were as varied as any across this great city.

-- Posted by Judy Levin

But this October 31, the Museum opened its doors for a special Family Halloween Celebration, and some unexpected specters were spotted in the halls.

The day began with cider and donuts, arts-and-crafts projects and a photo booth for vintage family photos. Large spotted spiders, cobwebs, and black crepe paper streamers turned the basement into a spooky party space.

Once guests were invited upstairs, they saw faces both old and new - Victoria Confino, part of the Confino Family Living History Tour, was busying about her kitchen as usual, but Harris Levine, Bridget Moore, and Rosaria and Adolfo Baldizzi were also at home this special morning.

All of our ghosts (In reality, costumed interpreters, of course) made charming hosts.

Victoria pointed out that our clothes looked pretty strange to her 1916 eyes: T-shirts and trousers on women seemed as peculiar as a young trick-or-treater dressed as a ballerina –

“You’re wearing your underwear on the outside?” Victoria asked about the tutu and tights. “Is that the custom where you come from?”

Bridget Moore, a tenant in 1869, was concerned that she couldn’t offer us tea. Harris Levine (who believed it was 1897) invited the 11-year-olds visiting his apartment to work full-time in his garment factory.

"Only ten hours a day - you can have the Sabbath off!"

Rosaria Baldizzi insisted that we call her Sadie.

“I have an American name now,” she explained.

She was packing and lamented the tenants’ recent eviction from the building after the new (1934) law requiring landlords to fireproof staircases in all tenements. The building, she reminded us, had been her home for many years. Her husband, Adolfo, mentioned their move too but was looking forward to the change.

For those of us who gives tours of the building, meeting this cast of characters in the flesh was unexpectedly moving. Even though those apparitions were just our coworkers in period costumes, they were a reminder that the stories we tell are true ones, that people really did live at 97 Orchard, and that their lives were as varied as any across this great city.

-- Posted by Judy Levin

Labels:

97 Orchard Street,

confino family,

Tenement Museum

Friday, November 6, 2009

Artifacts found in 97 Orchard Street's basement

Here is a follow-up to Wednesday's post about work in the basement of 97 Orchard Street. Our collections manager Derya describes what she found.

I think this research brings up an interesting question that many museums, over our history, have dealt with - how do you determine what is valuable and what is not? What kind of things should have protection and care in a museum's collection? Some folks might look at these bits of paper and plastic and wonder why we're bothering to save them. Do you think they have any value? What sort of objects do you think museums should be collecting?

- posted by kate

I think this research brings up an interesting question that many museums, over our history, have dealt with - how do you determine what is valuable and what is not? What kind of things should have protection and care in a museum's collection? Some folks might look at these bits of paper and plastic and wonder why we're bothering to save them. Do you think they have any value? What sort of objects do you think museums should be collecting?

- posted by kate

Thursday, November 5, 2009

The Snakehead - Tenement Talk Review

Patrick Radden Keefe was studying for the bar exam in the summer of 2005 when he first heard about Sister Ping, a woman whose story had captivated many in the legal community. On the surface, she seemed fairly ordinary: an immigrant from the Fujian province of China Hester Street New York

She was a snakehead — an “immigration broker” who smuggled people from one country to another. It is estimated that she made approximately $40 million in her ingenious—albeit dangerous and illicit—scheme. But in the summer of 2005, Sister Ping’s actions were finally met with retribution when she was convicted and sentenced to 35 years (likely the rest of her life) in prison.

Keefe details Sister Ping’s incredible narrative in his new book, The Snakehead: An Epic Tale of the Chinatown Underworld and the American Dream. Speaking at a Tenement Talk on October 27th, the author noted that the museum was the “perfect place” to discuss Sister Ping’s story, an odd permutation of the American dream that reveals “a chapter in immigration history” that may be unfamiliar to many.

Born in China New York China to the US

One such ship, the ill-fated Golden Venture, ran aground off Queens on June 6, 1993, after an arduous 120 days at sea with 300 Fujianese in its hull. When the dust settled, ten passengers were dead, the rest were detained, and Sister Ping was indicted for her involvement. Shortly after, she fled the country, leaving a wake of controversy with some unlikely players and leading to an FBI investigation that ended in her eventual apprehension in Hong Kong in 2000.

Keefe spoke to the audience about his research process, which included hundreds of interviews with many of those involved, including Sister Ping’s gang associates, law enforcement officials, and Golden Venture passengers and their lawyers. Upon traveling to China Chinatown echoed those positive sentiments, holding her to a “Robin Hood” status.

When asked about his own feelings towards Sister Ping, Keefe was not quite as forgiving. “Robin Hood wasn’t in it for the money,” he said. He did note, however, that she was a brilliant business woman with a knack for seeing a need and filling it, not unlike many other successful immigrants have in the past. And there is little doubt that other snakeheads have now filled the void left by Sister Ping. While there is no accurate data on the number of people currently leaving the Fujian province for the US

Sister Ping’s story may be unique, but it is tied to this larger theme, which is why Keefe’s book is a definite must-read for anyone interested in immigration issues in theUS

Sister Ping’s story may be unique, but it is tied to this larger theme, which is why Keefe’s book is a definite must-read for anyone interested in immigration issues in the

For the fascinating account of Sister Ping’s story, check out Patrick Radden Keefe’s The Snakehead: An Epic Tale of the Chinatown Underworld and the American Dream, available online or at the Tenement Museum Shop at 108 Orchard Street.

- Posted by Kristin Shiller, Orchard Street Contemporaries volunteer.

The Orchard Street Contemporaries is a group of young professionals committed to advancing the mission of the Tenement Museum by connecting the immigrant history of the LES to the vibrancy of the neighborhood today through social events, networking and museum programming.

The group provides a forum for exploration of our nation’s immigrant heritage, and what that means for us now. For more info, fan the OSC on Facebook or join the mailing list by emailing osc@tenement.org.

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Urban Archeology at the Tenement Museum

No one ever said museum work was glamorous. Here's Derya, the Museum's collections manager, discussing her work in the basement of 97 Orchard Street.

Tomorrow or Friday we'll share what small treasures she's discovered...

Tomorrow or Friday we'll share what small treasures she's discovered...

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

Work has begun on our Storefronts exhibit!

In addition to starting work on the rear yard exhibit, we have also begun serious work on Schneider's Saloon, which has long been in the planning and research stages. If you subscribe to our newsletter, you may have read about this exhibit already.

In 97 Orchard Street's basement, from 1864 until the late 1880s, John Schneider ran a lager bier saloon. This was a place for food and drink but also socialization, political discussions, and families to spend time together. We'll be reconstructing the saloon but also discussing some of the other businesses that were once housed in 97 Orchard, including a butcher shop and auction house.

Earlier in the summer, Jablonski Building Conservation completed some architectural probes in the basement. Now we've dived in even more, removing large sections of sheetrock on the walls to see what we can find underneath. The existing historical fabric is largely intact from decades earlier. Even seemingly insignificant information (like whether a column is painted all the way around or whether there is decorative woodwork on the ceiling) can tell us how the space was used at different times in history.

We found evidence of wallpaper in the north-rear room, which is used for storage (see Chris and Bob at work in the slideshow below). This is significant because it suggests that there were rear apartments in the basement space, something the Museum had suspected but never confirmed with physical evidence. In the late 19th century, wallpaper was largely identified with residential spaces, not commercial.

In all likelihood, there were two apartments in the rear and a large storefront up front, which in the mid-19th century would have been the saloon. The Schnieders may well have lived in back. Sometime in the 1890s, it seems the storefront space was subdivided into two, but the apartments probably remained for a bit longer, and the storekeeps may still have lived in back of the store. Eventually they were cleared out completely and both sides of the basement were turned over to storefronts.

Here are some photos from the space. Later this week, I'll post more on the work.

- Posted by Kate

In 97 Orchard Street's basement, from 1864 until the late 1880s, John Schneider ran a lager bier saloon. This was a place for food and drink but also socialization, political discussions, and families to spend time together. We'll be reconstructing the saloon but also discussing some of the other businesses that were once housed in 97 Orchard, including a butcher shop and auction house.

Earlier in the summer, Jablonski Building Conservation completed some architectural probes in the basement. Now we've dived in even more, removing large sections of sheetrock on the walls to see what we can find underneath. The existing historical fabric is largely intact from decades earlier. Even seemingly insignificant information (like whether a column is painted all the way around or whether there is decorative woodwork on the ceiling) can tell us how the space was used at different times in history.

We found evidence of wallpaper in the north-rear room, which is used for storage (see Chris and Bob at work in the slideshow below). This is significant because it suggests that there were rear apartments in the basement space, something the Museum had suspected but never confirmed with physical evidence. In the late 19th century, wallpaper was largely identified with residential spaces, not commercial.

In all likelihood, there were two apartments in the rear and a large storefront up front, which in the mid-19th century would have been the saloon. The Schnieders may well have lived in back. Sometime in the 1890s, it seems the storefront space was subdivided into two, but the apartments probably remained for a bit longer, and the storekeeps may still have lived in back of the store. Eventually they were cleared out completely and both sides of the basement were turned over to storefronts.

Here are some photos from the space. Later this week, I'll post more on the work.

- Posted by Kate

Monday, November 2, 2009

Work has begun on Rear Yard exhibit!

This week we started construction on the rear yard.

If you ever walked by in the past, or took The Moores: An Irish Family in America tour, you probably remember that the yard looked something like this:

The flagstones (stacked up around the edge) were removed from the yard. The large pieces of stone are architectural details from the old Daily Forward building, which the Museum salvaged when the building was being renovated into condos.

While the stone details will be put into storage, we're planning to use the flagstones in the restoration. We're building the wooden privy shed against that cinder block wall, installing a water pump next to that, and putting up a wooden fence around the yard, similar to what you see here:

This is Fanny Rogarshevsky and her son Sam in 97 Orchard Street's rear yard, early 20th century, but date unknown.

Here's what we plan for the final exhibit to look like:

The water pump is there on the left. Until well into the 20th century, there was a row of tenements up against ours on what is now the sidewalk and northbound traffic lane of Allen Street, so this image really does give a good sense of what our yard probably looked like circa 1904, when this photo was taken. (Courtesy New York Public Library, original source New York City Tenement House Department).

Here are some more photos from the NYPL to give you a better sense of what the privy shed will look like. (Warning, I'm sending you down a time-suck rabbit hole if you like looking at old pictures from the Tenement House Department - they're pretty interesting, and there are lots of them in the NYPL's collection.)

There will also be laundry lines and wash buckets to simulate the activity that would have constantly been going on in this space (for years, the only source of water for the building was the rear yard water pump, and the only toilets were back here, so you can imagine how many people would have been in and out all day long).

The restoration will be semi-visible from the street and will enhance The Moores tour by giving some context to the discussion about health and sanitation in tenement housing. For now, there are no plans for it to be its own free-standing tour or exhibit.

We'll keep you posted as work continues. We should be done in a few weeks!

- Posted by Kate

The flagstones (stacked up around the edge) were removed from the yard. The large pieces of stone are architectural details from the old Daily Forward building, which the Museum salvaged when the building was being renovated into condos.

While the stone details will be put into storage, we're planning to use the flagstones in the restoration. We're building the wooden privy shed against that cinder block wall, installing a water pump next to that, and putting up a wooden fence around the yard, similar to what you see here:

This is Fanny Rogarshevsky and her son Sam in 97 Orchard Street's rear yard, early 20th century, but date unknown.

Here's what we plan for the final exhibit to look like:

The water pump is there on the left. Until well into the 20th century, there was a row of tenements up against ours on what is now the sidewalk and northbound traffic lane of Allen Street, so this image really does give a good sense of what our yard probably looked like circa 1904, when this photo was taken. (Courtesy New York Public Library, original source New York City Tenement House Department).

Here are some more photos from the NYPL to give you a better sense of what the privy shed will look like. (Warning, I'm sending you down a time-suck rabbit hole if you like looking at old pictures from the Tenement House Department - they're pretty interesting, and there are lots of them in the NYPL's collection.)

There will also be laundry lines and wash buckets to simulate the activity that would have constantly been going on in this space (for years, the only source of water for the building was the rear yard water pump, and the only toilets were back here, so you can imagine how many people would have been in and out all day long).

The restoration will be semi-visible from the street and will enhance The Moores tour by giving some context to the discussion about health and sanitation in tenement housing. For now, there are no plans for it to be its own free-standing tour or exhibit.

We'll keep you posted as work continues. We should be done in a few weeks!

- Posted by Kate

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)