Thursday, August 23, 2012

We've Moved!

After more than four years, the "Notes from the Tenement" blog has moved! Please visit us at http://www.tenement.org/blog/ for the latest posts. You can continue to visit this address to view past articles as well.

Monday, August 13, 2012

Shopping for History

The historic shops at 97 Orchard Street were busy places, crammed full of people and goods. To recreate these environments for our "Shop Life" exhibit, we've done a bit of shopping ourselves, collecting historic objects to help us tell stories from dating all the way back to the 1860's.

Kathleen O'Hara, Collections Manager and Registrar, recently revealed some of these objects. Here are some of the highlights:

We know that, in the late 19th century, 97 Orchard Street resident and shopkeeper John Schneider was a member of the Improved Order of Red Men, a fraternal organization that modeled many of its practices after Native American customs. The Red Men were known to dress in feathered headdresses, apply paint to their faces and collect artifacts associated with Native American culture. While Native Americans would have used this type of club as a weapon, for members of the Order of Red Men like John Schneider, this would have been a souvenir and symbol of the fraternity.

What would a German saloon be without a beer barrel? Nineteenth century German saloons were family-friendly gathering places on the Lower East Side. While beer may have been the main attraction for parents of both sexes, whole families gathered in saloons like the one at 97 Orchard Street to enjoy home cooked meals and a lively atmosphere after a long day.

Kathleen O'Hara, Collections Manager and Registrar, recently revealed some of these objects. Here are some of the highlights:

Iroquois war club, Schnieder's Saloon

Beer barrel, Schieder's Saloon

What would a German saloon be without a beer barrel? Nineteenth century German saloons were family-friendly gathering places on the Lower East Side. While beer may have been the main attraction for parents of both sexes, whole families gathered in saloons like the one at 97 Orchard Street to enjoy home cooked meals and a lively atmosphere after a long day.

Sash and bundle of sticks, Schnieder's saloon

These objects are part of the regalia associated with the Oddfellows, another fraternal organization that congregated in the back rooms of saloons on the Lower East Side. The sash is made of velvet with intricate beaded designs. The bundle of sticks is a symbol which can be traced to ancient Roman concepts of strength and unity.

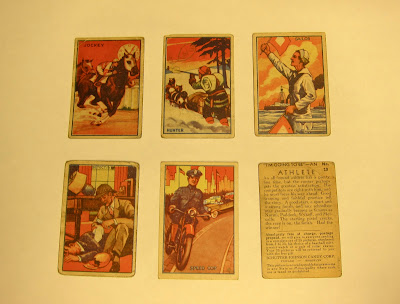

Trading Cards

These trading cards from 1934 were manufactured by the Schutter Johnson Candy-Corp. Collectors of all 25 designs could trade the cards in for various prizes such as a baseball mitt, a wristwatch, or roller skates. Cards depicting a detective, a policeman, a jockey, a hunter, a sailor, and an athlete are included in the Tenement Museum’s collections.

Microphone, Max Marcus' Auction House

A microphone like the one above would have been used by auction-house owners like 97 Orchard Street’s Max Marcus. The microphone, when plugged into a radio, would broadcast the auctioneer’s voice throughout the room. In this image of Marcus' crowded auction house from 1933, we can imagine that it might have been hard to hear Max’s voice even with the microphone!

Undergarments, Sidney's Undergarments

In the 1970s, the Meda family started their own business in the basement of 97 Orchard Street selling ladies undergarments, called Sidney Undergarments Co. These colorful underwear were given to the Museum by the Medas themselves. While these objects will not be on display for Shop Life, they give the curatorial team insight into the styles and prints that were popular at the time.

This is just a fraction of the cool items we have as part of our "Shop Life" collection. We'll keep you posted as we get closer to the exhibit's opening on October 1!

-- Posted by Ana Colon

Thursday, August 2, 2012

Home Remedies from Back in the Day

Summer might bring great weather and shorter work hours, but it can be pretty rough on our bodies. Despite modern medicine and simple solutions found at the local drugstore, sometimes you can’t prevent falling under the weather.

Instead of (or in addition to) Theraflu and Hall's, some people treat their maladies with old school cures passed down from their abuelas and bubbies, or further up the line from their ancestors.

|

| Image Courtesy New York Public Library |

If you flip through The First Jewish-American Cookbook, published in 1871, you'll find a section dedicated to household cures for pesky seasonal illnesses. Here’s what Mrs. Esther Levy, the author of the book, suggests for our summer woes:

For that cold that sneaked up on you:

“Bathe the feet in warm water; if feverish, take a glass of hot milk with a tablespoonful of the best whiskey and a tablespoonful of lime water, sweetened with sugar; and in the morning, fasting, one tablespoonful of castor oil in milk. Be careful about exposure next day.”

For that cramp you got after getting lost on your way to a subway station:

“Stretch out the heel as far as possible, and at the same time draw the toes as much as possible towards the leg; it will give relief.”

For those mysterious mosquito bites you wake up to every morning:

“Put into a glass or basin of cold water, one ounce of alum, a handful of salt, and two tablespoonfuls of vinegar; run it on at night, and let it dry in the flesh.”

|

| Image Courtesy New York Public Library |

Feeling inspired by any of these Jewish-American remedies? Were you taught any special cures like these from an elder in your family? Tell us in the comments!

-- Posted by Ana Colon

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

A Shop Comes to Life at 97 Orchard

It's been exactly two months since we posted our last update on the "Shop Life" exhibit, and things are moving along quickly! The dust, plywood and puzzling artifacts have been removed; in their place a gleaming new space is emerging on the ground floor at 97 Orchard Street.

Everything--from paint color to floor finish and hardware--has been carefully selected to represent the era accurately. The finish work is being overseen by restoration craftsman and all-around Renaissance man Kevin Groves.

We'll be furnishing this space to re-create John and Caroline Schneider's German beer saloon, which served up lager and lunch in the 1870's.

Next, Kevin's constructing built-in furniture, starting with the bar and back bar. Once these are complete, Curator Pam Keech will begin filling the space with the objects that bring it to life--including expertly crafted faux food and carefully selected historic artifacts.

"Shop Life" is scheduled to open this October--we hope you'll join us for a tour!

-- Posted by Kira Garcia

Everything--from paint color to floor finish and hardware--has been carefully selected to represent the era accurately. The finish work is being overseen by restoration craftsman and all-around Renaissance man Kevin Groves.

|

| Kevin Groves at work |

We'll be furnishing this space to re-create John and Caroline Schneider's German beer saloon, which served up lager and lunch in the 1870's.

|

| The once and future Schneider's saloon |

Next, Kevin's constructing built-in furniture, starting with the bar and back bar. Once these are complete, Curator Pam Keech will begin filling the space with the objects that bring it to life--including expertly crafted faux food and carefully selected historic artifacts.

"Shop Life" is scheduled to open this October--we hope you'll join us for a tour!

-- Posted by Kira Garcia

Thursday, July 26, 2012

A Room With a [Legally Mandated] View: Housing Laws at 97 Orchard

This post explores the legislation behind the design of tenement houses, and how changes in regulations can be seen at 97 Orchard Street. The Tenement Museum's “Hard Times” tour visits two apartments occupied during different periods of tenement house legislation— before and after the New Law of 1901.

97 Orchard is a pre-“Old Law” tenement, which means it was constructed before the passage of Tenement House Law of 1867 (the “Old Law”). This was the first law of its kind, listing requirements for adequate living conditions within tenement buildings.

In 1901, the “New Law” requiring vast changes to buildings like 97 Orchard Street, (called “dumbbell tenements,” because of their shape), in an effort to improve the health and safety of residents. Dumbbell tenements were built for maximum occupancy, not for quality. Their structure was simple: four 325-square-feet apartments per floor, three rooms per apartment, and a window that wouldn’t necessarily let in much light or air. The Gumpertz family occupied their second story apartment from 1870 to 1883, just prior to the passage of the New Law, so they wouldn't have enjoyed the resulting upgrades.

These reforms targeted specific (and unpleasant) aspects of tenement life, such as lack of ventilation and light, and sanitation of bathrooms. The New Law of 1901 meticulously described how every inch of a tenement house should look and function. The result was greatly improved ventilation, sanitation, and safety.

Here are a couple of the law's key provisions. They make distinctions between pre-existing buildings (like 97 Orchard) and new construction:

Does this sash window sound familiar? If you’ve visited the Baldizzi’s apartment, right next to the Gumpertz’, you might have noticed that there's one over the kitchen table. The Baldizzis occupied this apartment between 1928 until 97 Orchard closed in 1935. It showcases the physical changes required by the new law. After paying a visit to the Gumpertz’, the Baldizzi’s apartment is noticeably more airy and better lit.

If you exit the Baldizzi apartment and look down the hallway to your left, you’ll see another important upgrade--a bathroom. They're not pretty, but these inside toilets were a significant upgrade from the outhouses set up in the yards behind tenements.

In the 1930's, housing laws required further upgrades that proved too costly for some landlords, so many buildings, including 97 Orchard, were closed rather than renovated. In 1935, the residents of 97 Orchard were evicted, and the tenement closed its doors to residents for the last time.

-- Posted by Ana Colon

97 Orchard is a pre-“Old Law” tenement, which means it was constructed before the passage of Tenement House Law of 1867 (the “Old Law”). This was the first law of its kind, listing requirements for adequate living conditions within tenement buildings.

In 1901, the “New Law” requiring vast changes to buildings like 97 Orchard Street, (called “dumbbell tenements,” because of their shape), in an effort to improve the health and safety of residents. Dumbbell tenements were built for maximum occupancy, not for quality. Their structure was simple: four 325-square-feet apartments per floor, three rooms per apartment, and a window that wouldn’t necessarily let in much light or air. The Gumpertz family occupied their second story apartment from 1870 to 1883, just prior to the passage of the New Law, so they wouldn't have enjoyed the resulting upgrades.

|

| The Gumpertz family resided at 97 Orchard Street prior to the "New Law" upgrades |

These reforms targeted specific (and unpleasant) aspects of tenement life, such as lack of ventilation and light, and sanitation of bathrooms. The New Law of 1901 meticulously described how every inch of a tenement house should look and function. The result was greatly improved ventilation, sanitation, and safety.

Here are a couple of the law's key provisions. They make distinctions between pre-existing buildings (like 97 Orchard) and new construction:

Chapter III “Light and Ventilation”, Title I, Section 67: Rooms, lighting, and ventilation of.— In every tenement house hereafter erected every room, except water-closet compartments and bathrooms, shall have at least one window opening directly upon the street or upon a yard or court. (New Law, 29)

Chapter III, Title II “Provisions applicable only to now existing Tenement Houses”, Section 79: Rooms, lighting, and ventilation of, continued.— No room in a now existing tenement house shall hereafter be occupied for living purposes unless it shall have a window upon the street, or upon a yard no less than four feet deep, or upon a court or a shaft of no less than twenty-five square feet in area, open to the sky without roof or skylight, or unless such room has a sash window opening into an adjoining room in the same apartment said sash window having at least fifteen square feet of glazed surface, being at least three feet by five feet between stop beads, and at least one-half thereof being made to open readily. An alcove opening of no less dimension than said sash window shall be deemed its equivalent. (New Law, 33)

Does this sash window sound familiar? If you’ve visited the Baldizzi’s apartment, right next to the Gumpertz’, you might have noticed that there's one over the kitchen table. The Baldizzis occupied this apartment between 1928 until 97 Orchard closed in 1935. It showcases the physical changes required by the new law. After paying a visit to the Gumpertz’, the Baldizzi’s apartment is noticeably more airy and better lit.

|

| The "New Law" required interior windows like this one in the Baldizzi kitchen. |

If you exit the Baldizzi apartment and look down the hallway to your left, you’ll see another important upgrade--a bathroom. They're not pretty, but these inside toilets were a significant upgrade from the outhouses set up in the yards behind tenements.

|

| Sure, it's humble, but it's better than an outhouse! |

In the 1930's, housing laws required further upgrades that proved too costly for some landlords, so many buildings, including 97 Orchard, were closed rather than renovated. In 1935, the residents of 97 Orchard were evicted, and the tenement closed its doors to residents for the last time.

-- Posted by Ana Colon

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Coney Island, Through the Photographer's Lens

Like generations of New Yorkers and tourists before me, I made my annual summer pilgrimage to the Coney Island Boardwalk two weeks ago to eat a hot dog at Nathan’s, smell the salty air and take in the sights.

Jacob Riis, one of the pioneering social activists of the mid-nineteenth century, took this image of children playing at the Coney Island beach in 1895. At the time this photograph was taken, cameras were heavy and required cumbersome equipment, like the detachable flash--which had only recently come to the United States from Germany. But on his trip to Coney Island, Riis could do without the flash and other components, relying on the natural light of a sunny day at the beach.

The image’s clarity and suffusion of light is notably different from Riis’s better known images, those of tenement life. However, like in his photos of the tenements, the children seem unaware or disinterested in the photographer in their midst, concentrating on collecting driftwood and splashing in the waves.

The children’s modest beach attire is a stark contrast to the scantily clad figures captured by another famous portrait photographer, Diane Arbus, sixty years later. Like Riis, Arbus was interested in capturing ordinary people, often those who were socially marginalized, in ordinary moments. Arbus, however, focused on capturing and analyzing her subjects’ psychological states.

Two of Arbus’s more well-known images are currently on display in the Naked Before the Camera exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Images like Arbus’s and Riis’s inform historians’ understandings of not only what places like Coney Island looked like but also the attitudes of people at that time towards their environments and the arts.

-- Posted by Hilary Whitham

|

| Jacob A. Riis, Playing by the Water, 1895 Image courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York |

Jacob Riis, one of the pioneering social activists of the mid-nineteenth century, took this image of children playing at the Coney Island beach in 1895. At the time this photograph was taken, cameras were heavy and required cumbersome equipment, like the detachable flash--which had only recently come to the United States from Germany. But on his trip to Coney Island, Riis could do without the flash and other components, relying on the natural light of a sunny day at the beach.

The image’s clarity and suffusion of light is notably different from Riis’s better known images, those of tenement life. However, like in his photos of the tenements, the children seem unaware or disinterested in the photographer in their midst, concentrating on collecting driftwood and splashing in the waves.

The children’s modest beach attire is a stark contrast to the scantily clad figures captured by another famous portrait photographer, Diane Arbus, sixty years later. Like Riis, Arbus was interested in capturing ordinary people, often those who were socially marginalized, in ordinary moments. Arbus, however, focused on capturing and analyzing her subjects’ psychological states.

|

| Diane Arbus, Two Girls in Matching Bathing Suits, Coney Island, N.Y., 1967 Image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Photography |

In this image, “Two Girls in Matching Bath Suits,” from 1967, the girls’ shared bathing suit accentuates their different attitude towards Arbus as photographer, and us as the viewer. The girl in the left of the frame faces the camera head on, tilting her head coyly, while the girl at the right turns her body away from the camera lens, pursing her lips in contrast to her companion’s slight smile. These young women, unlike the children in Riis’s photo, are aware of the photographer’s presence—and are clearly responding to it.

Two of Arbus’s more well-known images are currently on display in the Naked Before the Camera exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Images like Arbus’s and Riis’s inform historians’ understandings of not only what places like Coney Island looked like but also the attitudes of people at that time towards their environments and the arts.

-- Posted by Hilary Whitham

Thursday, July 19, 2012

Humans of New York: Turn of the Century Edition

Humans of New York, a self-proclaimed “photographic census of New York City”, has become a social media sensation over the past few months. Brandon Stanton, the photographer behind the ambitious project, captures residents and visitors of the five boroughs, highlighting their diversity in dress, heritage, hairstyle, and attitude. This unofficial record of the ever-changing face of New York City isn't the first photography project to document the people that roam New York City.

In the early 20th century, as large waves of immigrants were coming to New York to start new lives in a promising country, Augustus Francis Sherman photographed newly arrived immigrants as they passed through Ellis Island to officiate their entrance into the United States. He worked as the Ellis Island Chief Registry Clerk, and probably began taking these photographs at the request of the Commissioner of Immigration for the Port of New York at Ellis Island at the time, William Williams. Now in the trustworthy hands of the New York Public Library, these pictures once graced the pages of National Geographic (1907) and the walls of the lower Manhattan headquarters of the Federal Immigration Service.

While these portraits give us an idea of what people looked like as they entered their new lives in a strange country, it is very possible that they were partially staged by Sherman. Some subjects might have been detainees, while others might have changed into their finest garments—generally reserved for holidays or special occasions—in order to up the portrait’s theatricality. In any case, they offer a rare but impressive insight into the real faces of the people that would come to shape our nation at the turn of the century (many of them settling on the Lower East Side of New York City!)

-- Posted by Ana Colon

Augustus Sherman,"Serbian Gypsies", ca. 1906;

Image Courtesy New York Public Library |

In the early 20th century, as large waves of immigrants were coming to New York to start new lives in a promising country, Augustus Francis Sherman photographed newly arrived immigrants as they passed through Ellis Island to officiate their entrance into the United States. He worked as the Ellis Island Chief Registry Clerk, and probably began taking these photographs at the request of the Commissioner of Immigration for the Port of New York at Ellis Island at the time, William Williams. Now in the trustworthy hands of the New York Public Library, these pictures once graced the pages of National Geographic (1907) and the walls of the lower Manhattan headquarters of the Federal Immigration Service.

While these portraits give us an idea of what people looked like as they entered their new lives in a strange country, it is very possible that they were partially staged by Sherman. Some subjects might have been detainees, while others might have changed into their finest garments—generally reserved for holidays or special occasions—in order to up the portrait’s theatricality. In any case, they offer a rare but impressive insight into the real faces of the people that would come to shape our nation at the turn of the century (many of them settling on the Lower East Side of New York City!)

|

| Augustus Sherman,"Albanian soldier", 1906-1914; Image Courtesy New York Public Library |

|

| Augustus Sherman,"Guadeloupean woman", 1911; Image Courtesy New York Public Library |

| Augustus Sherman,"German stowaway", ca. 1911; Image Courtesy New York Public Library |

|

Augustus Sherman, "Alsace-Lorraine girl",

ca. 1906; Image Courtesy New York Public Library |

|

| Augustus Sherman, "Dutch children", ca. 1905-1914; Image Courtesy New York Public Library |

-- Posted by Ana Colon

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)